30.12.22

First Knowledges

28.12.22

The Passion of Private White

I grabbed Don Watson's latest book, The Passion of Private White, from the library after hearing the author speak about it on the radio (the way I usually hear about new books these days). Ostensibly the story of Neville White, an anthropologist who has worked for many years in an Arnhem Land community and has ended by forfeiting his academic 'objectivity' to intertwine his own life with those of his Indigenous 'subjects,' The Passion of Private White is actually more about the Yolgnu people of Donydji -- their searing history, their complicated personal politics and their never-ending battles with well-meaning but inflexible and short-sighted bureaucracy.

This is a devastating book, setting out in Watson's limpid, carefully controlled prose, a litany of cultural clashes and personality conflicts, the history of a fifty year relationship between one man and a community, with all the trust and affection, the misunderstandings and jealousies and resentments, that any fifty year relationship contains. But the difference between Neville White and the other do-gooders from down south is that he has stuck around, finding a way to heal his personal Vietnam trauma through his deep involvement with Donydji, and drawing in some of his fellow veterans too. It's inspiring, but also dispiriting, to read about houses built and workshops set up by the veterans at a tenth of the cost and time that government contractors would take; and it's dispiriting, too, to see the failures of some of those efforts, because people are people, and things are complicated.

But there is hope here, too, of a different way of relating to people in remote communities and making things better -- with respect, and listening, and patience, and a stubborn, persistent kind of love.

26.12.22

The White Witch

I have no conscious memory of reading Elizabeth Goudge's The White Witch before, but I think I must have read it in high school, because in retrospect I'm sure I was influenced by certain elements of this novel. There is the English Civil War setting -- I went on to study the Civil War at university. There is Froniga's expertise in herbal cures, and especially her reading of the tarot cards, both subjects which sparked my imagination.

But I couldn't remember much of the actual plot, perhaps because, as usual with Goudge, there isn't a whole lot of action, despite being set during a war and even featuring a few battles. For Goudge, the really interesting struggles are all internal ones, like renouncing love or surrendering to God's will.

There are some aspects of this book which haven't aged well since 1958 when it was published, notably the painter Francis Leyland's romantic yearning for eight year old Jenny. Though they don't get together until the end of the book, when she is safely grown up, it's still, as the kids say, ick. But there are lots of parts I loved, particularly proud, competent Froniga (her name is a version of Veronica), who is really a heroine to look up to -- and I think I did!

I don't think Elizabeth Goudge ever wrote a novel, either children or adults, that doesn't feature children at its heart, and she does write them exceptionally well, whether it's self-possessed Jenny, her self-important twin Will, or the wild gypsy children who flock to Froniga 'like birds.'

22.12.22

The Shadow Guests

Another book I picked up in an op shop that I was delighted to discover. As a young reader, I fell in love with The Wolves of Willoughby Chase (and was lucky enough to have my copy signed by the author at The Little Bookroom), and also later became a fan of Dido Twite's adventures, as well as Aiken's wonderful short stories. But this standalone novel, 1980's The Shadow Guests, was new to me.

Poor Cosmo has come all the way from Australia, where his father had unsuccessfully tried to avoid a family curse, and meets a hostile reception at his new school. However, in the tradition of Green Knowe, the ancient family home of Courtoys Mill is far more welcoming, and Cosmo soon encounters several ghostly figures, who are all also victims of the curse on the family, and in their different ways, help him to deal with it.

This is quite a dark book, despite the echoes of Green Knowe; family tragedy, grief and loneliness hang over it. The modern reader shakes their head as Cosmo's new headmaster, quite wise in other ways, advises him not to talk about what he's been through. The meeting with seventeenth century Osmond, member of the Hellfire Club and dabbler in black magic, is also pretty scary, as is the sombre reality of the curse. But I loved cousin Eunice and her willingness to speculate on things beyond our ken, in spite of being a scientist.

The Shadow Guests is packed with characters and atmosphere and a great time-twisty premise, and I think it would appeal to contemporary readers and fans of time-slip and ghost stories as much as it did to me.

20.12.22

The Dolphin Crossing

The explosion stunned John...'Pat!' he called. 'Pat, where are you?''Here,' said a voice at his feet. Pat had been knocked over by the blast. He scrambled up again, and they looked for the little cruiser. There was not the smallest trace of her. Pat was looking at John in alarm. And John realised that there was a nasty, hot, wet feeling in his left arm. He looked down at it, and saw that he was pouring with blood. He felt weak and faint.

18.12.22

Our Castle By The Sea

The atmosphere of fear and suspicion in war-time was really well explored, though unfortunately the book was marred for me by the revelation of an almost pantomime villain at the very end. I did enjoy the twists and turns where seemingly friendly characters became untrustworthy, and sinister ones ended up being more heroic than they first appeared. I found this cover very appealing -- note the green-painted lighthouse, another detail I wasn't aware of previously. There is even a touch of the supernatural in Petra's relationship with the standing stones, the Daughters of Stone, and the dangerous sandbar called the Wyrm that haunts her dreams.

Our Castle by the Sea is a beautifully designed book that approaches questions of loyalty and betrayal from a fresh angle; and one spooky element for me was the description of the boat-shaped church that also featured in Storm Ahead.

13.12.22

To The Islands

To the Islands is a truly remarkable novel. Written when Stow was only 22 (!!), it won the Miles Franklin Award as well as the Australian Literature Society Gold Medal in 1958. It's extraordinary to think that this book was written 64 years ago and yet the issues that it deals with are still as thorny and relevant as ever: relationships between First Nations peoples and white colonisers; relationships to country; different kinds of knowledge; the anguish of dispossession and slaughter; inherited trauma.

To the Islands is a short novel, but not an easy one to read. Its pages are filled with pain. This might have been one of the first works of Australian fiction that treats Aboriginal people as fully rounded, complex characters in their own right, rather than as a backdrop to white drama. Stow stated that part of the intent of the book was to argue a case for supporting the church mission stations, which as he saw it, provided essential services, education and protection to the people dwelling on remote lands. Others may not agree with this assessment; but the fact remains, it's still a wickedly difficult problem to draw the balance between preserving culture and traditional knowledge of country, with access to medical help, educational opportunities and even basic services like power and water that other Australian citizens expect as their right.

To the Islands is an astonishing, insightful, angry and grief-filled novel from a very young author. I'm very glad to have read it.

10.12.22

French Braid

Anne Tyler is one of the most reliable authors I know -- I can pick up one of her novels with complete confidence that I'm in safe hands and that I will enjoy the ride. In French Braid, Tyler returns to familiar territory: an inter-generational family story set in the suburbs of Baltimore.

The novel opens in 2010, with an encounter at a train station between two cousins who haven't seen each other for a long time, setting up the slight mystery of why the members of this family don't stay in touch. (It says a lot for Tyler's powers that she can turn such a relatively (ha!) low stakes mystery into an utterly absorbing story.)

The following chapters swoop back and forward in time, from a rare family holiday by the lake in 1959 to Covid lockdowns in 2020, each chapter focused on a different member of the family and illuminating from a different angle the weird silences that lie between them. Mercy, the mother, has moved out of the family home, but it's never spoken about. David, the son, never comes home and leaves it to his new wife to announce their marriage. Candle, a grand-daughter, accompanies Mercy on a fateful trip to New York. But it's not until the very end of the novel that we discover the source of this peculiar, decades-long tension, and even then we're left unsure whether it was all a tragic misunderstanding.

I just love Anne Tyler, opening one of her novels is like slipping into a warm bath. In the past I have succumbed to the temptation to read too many in a row, and after about five books the charm began to wear thin (maybe the bath water grew cool, to stretch the metaphor). But as a treat, once in a while, there is nothing more enjoyable. Is there anyone better at capturing the unspoken undercurrents of family dialogues -- the meaning glances, the raised eyebrow, the forced cheer, the humour? Anne Tyler is a master.

8.12.22

Storm Ahead

Storm Ahead by Monica Edwards was the other book I brought with me for my long train journey a couple of weeks ago. I ordered it from Girls Gone By, though I've never read it before, because it's part of the Romney Marsh series. As a kid, I absolutely adored the first two books in the series, Wish For a Pony and The Summer of the Great Secret, which I borrowed over and over again from the Mt Hagen library, and 'dreamed' about night after night while I was falling asleep. Having re-acquired and re-read them as an adult, I'm left faintly bemused by the source of my obsession. They are fairly standard pony books, albeit with attractive heroines in Tamzin and Rissa. I think it was the stable (see what I did there...), cosy and safe world that the girls inhabited that appealed to me most at a time when my family was moving fairly frequently.

Ironically, in Storm Ahead, the security of the village is threatened by wild weather. The book is based on a true and tragic incident which Edwards witnessed as a teenager, the loss of a lifeboat with all hands drowned, and the catastrophic flooding of the village. (The last element was particularly apt, as the train moved through flooded country around the Murray.) The action takes place over a hectic couple of days as the storm and flood sweep over the village, though there is a semi-optimistic ending suitable for a children's book as the young protagonists get to play Father Christmas to the stricken village children. Storm Ahead is also a crossover story, featuring Lindsey from Edwards' other popular series, Punchbowl Farm.

The writing is a bit more stilted than I remember from Edwards' other books (I think I can still quote bits of Summer of the Great Secret by heart!) but it was still a lovely nostalgic read, albeit with a grim event at its centre. The biographical notes provided by GGB were fascinating and definitely added to my appreciation of the story. Weirdly, another book I'm reading concurrently, Our Castle by the Sea, is also set on the Kentish coast, and also features a church with a roof 'like the hull of an upturned boat,' based on the real Rye Harbour church. More on Our Castle later...

5.12.22

The Year of Living Biblically

I picked up A. J. Jacobs' The Year of Living Biblically (original title: By the Book) from a street library, appropriately enough, outside a local church, and took it with me to read on the train between Sydney and Melbourne (11 hours of total relaxation, can't recommend it enough). A fellow passenger wearing a large crucifix caught sight of the cover and eagerly asked for a look; however, after a quick glance, she handed it back with a bemused expression, and I'm guessing it wasn't quite the book she thought it might be.

I, on the other hand, thoroughly enjoyed it. It falls into the category I call 'chatty memoir.' A.J. Jacobs is known for his immersive journalism; I'd previously enjoyed The Know-It-All, which chronicled his quest to read the entire Encyclopedia Brittanica. The Year of Living Biblically similarly follows Jacobs' attempt to follow every rule in the Bible. He grows his hair and his beard, refrains from touching his wife during certain times of the month, dresses in white, begins praying regularly, tries to stop lying (this is a particularly difficult injunction) and explores many more obscure Biblical rules, including animal sacrifice, scaring a pigeon off its nest and hunting for a flawless red heifer.

His conclusion is that every Bible-based religion and sect 'cherry-picks' because it's simply impossible to follow every rule, partly because they often contradict each other. A self-described secular Jew, he's also pleasantly surprised by a growing sense of spirituality, which maybe derives from a 'fake it till you make it' approach -- praying three times a day at first feels artificial and stilted, but in time he finds himself looking forward to prayer time and feeling genuine gratitude. Wearing white makes him feel 'lighter.' He begins to see the benefit of keeping the Sabbath, a day of rest, and giving to charity. And he also develops an unexpected sense of connection to his cultural heritage, and a couple of moments of transcendent joy.

A.J. Jacobs is a very funny, self-deprecating and acutely observant writer. His quest swings enjoyably between the very silly and the delightfully reflective. The Year of Living Biblically turned out to be a more thoughtful and deeper journey than I was expecting, and I'm guessing the same was true for Jacobs himself.

29.11.22

The Song of Achilles

It's not often that my younger daughter will wander through the living room, pick up a book I'm reading and say, 'Oh, I've heard about this.' The Song of Achilles has been an internet sensation. Between my borrowing it from the library and returning it, seven reserve requests had built up!

I decided to read The Song of Achilles after enjoying Madeline Miller's Circe, her second book, on the recommendation of my book club; but I think I ended up enjoying The Song of Achilles even more. I can certainly see why it's been such a hit with young adult readers. It's a vivid same-sex romance -- very sexy! -- set in ancient Greece, incorporating plenty of rich everyday detail but also a satisfying amount of interaction with the gods and spirits to create a wonderfully immersive alternate world.

The Trojan War dragged on for ten long years but we don't embark on the war itself until halfway through the book, and the long stay is mostly skimmed over. Miller uses the brilliant device of allowing us to continue to see the action even after our narrator Patroclus' death, as an unburied spirit lingers in our world and can still see the action. (Surely the name Patrick derives from Patroclus? I haven't been able to find confirmation of this anywhere but it must be true!)

The Song of Achilles is a thrilling retelling of a classic love story, and it truly does these shining young men justice.

24.11.22

The Big House

The Big House is in some ways a story of privilege -- the lovingly detailed history of one wealthy Boston family's beach house, a rambling weatherbeaten construction of (I think) nineteen rooms, surprising closets, random passageways, servants' bedrooms, a big sprawling house filled with family detritus, books and clothes and moth-eaten furniture and pennants and a tennis court... I must admit I began this book thinking, it's all right for some, mate.

But as the chapters unspooled, revealing family tragedy as well as privilege, and culminating in the disclosure that the family could no longer afford to keep the house (land tax alone was crippling, let alone the expenses of upkeep on a massive building that was literally beginning to fall apart), I became caught up in the struggle to hold onto the property, a place that kept the family secrets and the family memories.

It took me a long time to wander through The Big House and it ended up overlapping with Swann's Way, with which it shared some striking, perhaps intentional parallels. I'm sure Colt deliberately set out to emulate, in his painstaking descriptions of individual rooms, the cove, the woods, historic boat races and tennis tournaments, the loving detail that Proust brings to his own childhood memories of summers past. If Colt doesn't quite reach the heights of Proust, he does at least provide something closer to a narrative, in the story of the battle to save the house from demolition. The tone is definitely elegaic, a melancholy farewell to a vanished way of life.

21.11.22

Swann's Way

Swann's Way contains the very first part of the opus, the childhood memories and reflections of Combray (including the famous madeleine scene) as well as Swann in Love. Reader, I must confesss, I only reached the end of Combray before deciding that there are so many other books I would rather have been reading. There are certain activities that I'm still waiting to grow into -- gardening, listening to classical music, and now I have to include reading Proust to this list.

Having said that, I think I did enjoy this attempt more than the first. (Maybe Proust is an acquired taste, like olives and oysters, you just have to keep trying??) Taken in small nibbles, I could relax briefly into his exquisite, meandering, attenuated sentences that can wander over an entire page before gently coming to a halt. And I think I have a better understanding now of his feeling that an ideal image, preserved and relived in memory or constructed in the imagination, is superior to the experience of reality while it is being lived. (I suspect many anxious people would agree.) The descriptions are extraordinarily beautiful, transporting, subtle, and intense -- and yet there is a part of me that yearns for a story, and it's that part of me that refuses to be totally seduced by Proust.

I might give it another ten years and then try again...

16.11.22

When Things Are Alive They Hum

When Things Are Alive They Hum was published last year and is the debut novel of Australian author Hannah Bent (not to be confused with Hannah Kent), though Bent, like her character Marlowe, was born and brought up in Hong Kong and studied in London. The novel centres around Marlowe and her younger sister, Harper, who has what she calls 'Up' syndrome, and whose heart is beginning to fail.

This book had a personal resonance for me. My own younger sister has an intellectual disability (though her general health, touch wood, is very good) so elements of Marlowe and Harper's relationship came very close to home. I belong to a Facebook group for siblings of people with a disability, and I know from there, as well as from my own experience, that the sib relationship can be a particularly tangled knot of love, responsibility, resentment, guilt and protectiveness.

When Things Are Alive They Hum explores this complex connection with delicacy and nuance, while also diving into the very political and horrific issue of forced organ donation. I honestly didn't know which way the story was going to swing until the very end. This is a touching and emotional novel -- not just for sibs!

11.11.22

Being Mortal

I can't remember how I learned about American surgeon Atul Gawande's Being Mortal (probably a Facebook discussion), but it is a remarkable and thought-provoking read. Sub-titled Illness, Medicine and What Matters in the End, Gawande's book begins by discussing the advances of old age, and how to rethink what makes the end of life good, rather than just longer, and then moves into talking about terminal disease and similar issues there.

As a doctor, Gawande admits that he has often slipped into the role of 'Dr Information,' laying out treatment options, risks, benefits, side effects etc, and telling the bewildered, stressed patient to make a choice. Very few of us are well equipped to weigh up our options accurately, or even know what questions to ask, in such a situation. After observing skilled hospice and palliative care workers, Gawande has changed his approach, to ask what is most important to each individual patient -- prolonging life? Staying active? What would they be unwilling to trade off? What would make life no longer worth living? For one patient, being able to enjoy chocolate ice cream and watch football might be enough. Another might be unable to endure the risk of paralysis, or invasive medical treatments, or a greater level of pain. Gawande can then help the patient decide what approach is best for them, rather than just offering another treatment possibility, then another (there is always another treatment to offer).

With two elderly parents approaching the end of their lives and a friend in their final days, this felt like a particularly timely read, and one which has prompted me to think hard about what I want for myself in my last days. It's also made me determined to talk about this openly with my loved ones and not shy away from the difficult conversation. As Gawande points out, 'hard conversations can make wonderful things possible.' But it also makes my heart ache, because it's impossible to have this kind of nuanced conversation now with my father, because he just can't communicate with us well enough. I think I have a pretty good idea of his wishes now, but he can't spell them out for us in any detail. Don't leave it too late.

9.11.22

Treacle Walker

I was so excited when Alan Garner was nominated for the Booker Prize -- at 87, this may have been his last chance -- and I was disappointed when he didn't win it. However, having now read Treacle Walker, I have to agree with the critic who said while Garner may have deserved a Booker Prize, he didn't deserve it for this book. (I think The Stone Book is his masterpiece.)

Having said that, Alan Garner is a writer whose books are difficult to evaluate in isolation. He has said himself that he regards his novels as being one work, spread over a lifetime, ranging from the high fantasy of The Weirdstone of Brisingamen all the way to this sparse, elliptical work, which is closer to mystical poetry than a narrative novel. Barely 150 pages long, broken up with lots of blank space, this is a very short book indeed; and yet for readers of Garner's other books, it is dense with references, resonance and echoes of other stories, dancing on the edge of dream and reality. Perhaps the entire book is a fever dream; perhaps Joe is dying or actually dead; almost certainly Joe is an echo of Garner himself as a young boy, who spent much of his childhood ill in bed, reading and dreaming himself into stories.

Some readers have complained that there is no plot to this book; I don't agree, though the events are strange and enigmatic. Joe seems to live alone, we never see his parents or any other family, though he does take an eye test at one point. He encounters two mysterious figures, the wandering Treacle Walker and the bog-man Thin Amren, and I like the interpretation that these two characters also represent aspects of Garner himself -- Treacle Walker, the educated intellectual who went away to university, and Thin Amren, the deep-rooted Chesireman, steeped in folklore and fixed in place.

I'm not sure someone unfamiliar with Garner's body of work will find satisfaction in Treacle Walker. Some have called it obscure, self-indulgent, inaccessible, nonsensical, messy, incoherent. I enjoyed it and I will read it again. I've found this is essential to get the most out of Garner's recent work -- should this be necessary to enjoy a novel? Let's just say this book won't be for everyone, but for Garner's fans, this will be a deeply rewarding, meditative delight.

4.11.22

The Tell-Tale Heart

I was put onto Jill Dawson by a friend on-line; I hadn't heard of her before but she is a prolific English novelist. The Tell-Tale Heart (in large print) was, alas, the only title available from my library, but it was a terrific, thoughtful and very accomplished novel and I'm definitely going to keep an eye out for her other books.

The Tell-Tale Heart threads together three narratives -- the story of Patrick, a middle aged professor who has just received a heart transplant; swooping back a couple of centuries, the true history of a young man, Willie Beamiss, caught up in the Fen riots of 1823; and swooping forward again to Willie's descendant, Drew Beamish, the donor of Patrick's new heart. Connections between these three characters unfold and echo across the novel, and ultimately Patrick, despite his protestations, finds his life irrevocably changed by his experience.

I especially enjoyed the sections in the voice of Willy Beamiss, which were a delight to read and gave the book a real emotional and historical depth. These sections were based on court records from the Fen Riots, an episode in history about which I knew absolutely nothing; in fact, the Fen country in the east of England is an area I only know from books: Dorothy L. Sayers' The Nine Tailors, and Elizabeth Gouge's novels set in Ely. The Essex Serpent and Arthur Ransome's Secret Water have something of the same flat, marshy atmosphere, though technically they're not set in the Fens.

Another example of a weird book coincidence -- I found myself reading three books centred on hearts and death at the same time: The Tell-Tale Heart, When Things Are Alive They Hum (a young adult title about two sisters, one of whom needs a heart transplant) and Being Mortal, a non-fiction exploration of growing old and wearing out. Strange how these things happen, totally by chance!

2.11.22

The Goodbye Year

Now this is a cover I could fall in love with -- all my favourite colours, books, cats, cups of tea, trees a dog and a ghostly soldier, as well as a touch of golden spot gloss -- yum! My only tiny niggle is that Harper isn't wearing glasses... How I longed for more protagonists with glasses when I was a glum bespectacled 12 year old.

Inside the lovely cover, there is also much to enjoy inside Emily Gale's The Goodbye Year, which is perhaps my first full pandemic novel. As 2020 begins, Harper is looking forward to her final year at Riverlark Primary School, but then she's mown down by a truckload of changes. Her parents move oeverseas, leaving her with Lolly, the grandmother she barely knows; all her friends becomes school captains of something, leaving Harper with the dreggiest job, Library Captain (ahem, the best job, I think you mean.) And then Harper starts seeing things -- could there be a ghost in the old library?

I loved the parallels that Gale draws between the Covid pandemic and the Spanish flu, and the disruptions of war and the global upheaval that gripped all of us in 2020. Harper is a lovable character, her school friends are sweet, and William's story is spooky and moving. Gale doesn't dwell too long on the lockdowns themselves, focusing more on the periods of freedom in between, but not shying away from either the difficulties or the unexpected joys of a year that none of us will ever forget.

31.10.22

None Shall Sleep

New York Times bestseller! Go, Ellie Marney! One of Australia's very best YA authors, Marney produced a ripping mystery trilogy with her Every series, which I absolutely gulped down, and None Shall Sleep raises her bar still higher.

This book came out in 2020 but I must confess I was put off by the cover, which I think is... not great? But the words inside are brilliant. Marney acknowledges being a Mindhunter fan, and I also really loved the Netflix series and was hugely disappointed to learn that it hadn't been renewed after two seasons. Mindhunter was set in the earliest days of the Behavioural Science Unit of the FBI, when psychologists were first being employed to track 'multiple murders', better known now as serial killers. None Shall Sleep takes us into the FBI a few years later, to 1982, with a YA twist -- two teenagers, both survivors of trauma at the hands of a killer, are recruited to help the FBI gain some insight into young serial murderers.

I keep saying that I don't like horror, I don't like gore, and yet I seem to keep reading gory horror stories... None Shall Sleep gripped me from start to finish. There are shades of Hannibal Lecter and Clarice Starling's relationship in Emma and Simon's interactions, but they are very much their own characters. Marney is careful not to slip into horror porn with her descriptions of the repugnant actions of her killers -- the scenes are clearly horrific, but never explicit. Still, squeamish me wouldn't like to see any of this stuff on screen! The cover tagline reads 'a captivating and chilling psychological thriller' so I can't say I wasn't warned.

Gee, this was good.

29.10.22

Better Late Than Never

Emma Mahony's Better Late Than Never, part self-help manual, part memoir, is subtitled Understand, Survive and Thrive Midlife ADHD Diagnosis, and I borrowed it from the library because my elder daughter has a theory that her father might have ADHD tendencies, which does seem to be a possibility (in fact, his whole family definitely lean that way, now it's been pointed out). However, Mahony's book focuses primarily on the experience of women with later life diagnosis, which is something unfortunately not indicated in the title or on the cover. (The title is clever because ADHDers often struggle with punctuality!)

I found this a really interesting read, not least because of Mahony's unflinching honesty in looking back over her own life with the benefit of hindsight and seeing where her own ADHD has pushed her off track, ruined relationships, and blinded her to her son's own difficulties at school. But it's not all bad: ADHD has also given her gifts which have helped her to thrive in her career(s) and filled her life with variety and richness.

The three main characteristics of ADHD are restlessness, impulsivity and distractability, which Mahony reframes as creativity, energy and spontaneity, all of which can be invaluable traits if managed properly. Much of Better Late Than Never is a plea for greater understanding, especially of school children, which her mid-life career change to teaching has enabled her to see particularly clearly, though interestingly she often butts heads with authority in trying to help her fellow ADHDers. Published in the UK, the book's specific advice won't always apply to an Australian setting, but it's an insightful and fascinating glimpse into the condition.

27.10.22

How To Spell Catastrophe

I already knew that Fiona Wood was an author of superb young adult fiction (see Cloudwish, Six Impossible Things, Wildlife etc) and a really lovely human being (she once sought me out in an airport to invite me to sit with her in the Qantas lounge), but it turns out she can also write superlative novels for middle grade, too. * shakes fist at the sky* Damn you, Fiona Wood! Is there anything you can't do??

How To Spell Catastrophe is smart, warm, funny, subtle children's literature. Nell is in her final year of primary, that complicated time, half itching to move forward into the big new world of high school and the future, half clinging to the safety of the familiar, as she's torn between her old friends and the excitement of lawless new girl Plum. Nell's family is changing, too, when her mum proposes melding their cosy dyad with her boyfriend Ted and his younger daughter Amelia -- an idea which horrifies Nell. To cap it all off, Nell is a worrier, and jots down plans for dealing with any and all possible emergency situations. (I liked the way Nell's therapy sessions are discussed with a matter-of-fact lack of drama, as just another part of her life.) But climate change is such a big worry that it won't even fit into Nell's notebook --

There is so much to love about this book. Wood's writing is top notch, as you'd expect, and she is especially good on the dynamics of friendships. In a lesser novel, Plum might be a 'bad' person -- and she is problematic, encouraging Nell into reckless and irresponsible behaviour, being a bit mean sometimes -- but in Wood's hands the reader sees that Plum has her own issues to deal with, and perhaps what she really needs is a stable, cautious friend like Nell. Change is scary, and How To Spell Catastrophe handles the need to balance courage, careful planning, boldness and prudence in a really beautiful way.

(Ironically I managed to misspell 'catastrophe' twice while writing this post.)

25.10.22

Shadowlands

I found out about Matthew Green's Shadowlands through Susan Green's blog. We have very similar taste, and if she ever gives up blogging about the books she reads, I think I will, too, because at this point I am pretty much blogging purely for book recs...

ANYWAY, Shadowlands is creepy and eerie and poetic and melancholy. Apparently Green was going through some personal upheaval at the time he was writing and researching this book (the death of a parent, the breakdown of a marriage) and it shows. Shadowlands is partly a physical exploration of these abandoned settlements (buried Neolithic houses, plague villages, victims of coastal erosion, areas taken over for military simulations) and partly a history of Britain. The book is arranged in chronological order, so it serves as an eclectic timeline of Britain's crises and disasters, mostly wars and epidemics, to end with Green's gloomy reflection that there are probably towns and villages in Britain today just waiting to be deserted for whatever reason -- perhaps a nuclear disaster, or another epidemic, or most likely victims of climate change.

I do believe most of what Green tells us, but I have to point out that his account of St Kilda, the bayside suburb of Melbourne, being founded by refugees from the Scottish island of St Kilda, is unfortunately just plain wrong -- it was named after a steamship moored offshore (which admittedly was itself named after the island). So perhaps it's kind of true?

Shadowlands seems particularly poignant and timely as Victoria, having endured catastrophic bushfires a couple of summers ago, is currently in the middle of a slow flood calamity as one town after another waits for the rivers to peak and subside. This was a beautiful but sobering read.

21.10.22

The Prisoner

Jane Caro cited Kerry Tucker's memoir, The Prisoner, as a helpful source when she was researching her novel, The Mother, which I also read recently. The Prisoner was an absolutely fascinating and enlightening glimpse into a world which I know very little about. Kerry Tucker was an ordinary suburban mum (albeit with a painful personal history of sexual abuse) who fell into an ever-deeper spiral of debt and fraud, until she was finally convicted and received a fourteen year sentence, longer than some women who were convicted of murder (she was out a lot earlier on parole).

Yet again in my recenr reading, there were women in Kerry's prison who had killed abusive partners. She mixed with women from Melbourne's gangster underground, drug addicts, tough women and vulnerable women, women with intellectual disabilities (who shouldn't have been in prison at all), women with mental illness. There were kind prison officers and brutal prison officers. Kerry's descriptions of her experience are straightforward and unflinching; prison is no luxury resort, and the greatest punishment is separation from loved ones. Kerry finds being parted from her two young daughters especially painful.

And yet her account of her own years in prison is definitely positive. For the first time in her life she finds a clear purpose and place to belong, writing parole letters for her fellow inmates and eventually working as a peer support officer -- a counsellor, liaison with authority, problem solver, trouble shooter, go-between, legal and life adviser. As a middle class and articulate woman, she could offer gifts of practical common sense and language, and for once in her life, found herself indispensable. She should have been moved to a low security facility, but she was so useful that she was kept where she was.

The Prisoner does not gloss over the pain and trauma of incarceration, but Tucker maintains that 'prison works.' Maybe, if you have someone like her by your side... I'm not so sure. Still, I learned a lot from this book.

19.10.22

Never Forget You

Never Forget You is yet another WWII story (I seem to be on a bit of a binge at the moment!), but this novel focuses on four women, school friends who end up following very different paths through the war -- from working in the French Resistance in Paris, to flying planes, to infiltrating fascist groups within England itself. One of the characters is a real person, Noor Inayat Khan, though Gavin fictionalises aspects of her life. Inspired by reading this novel, I went on to watch the movie A Call to Spy on Netflix, which also features Noor's experiences (warning: it's pretty sad).

Unlike The Castle on the Hill, Never Forget You doesn't pull its punches -- not all the friends make it safely through the war. With her links to India, Gavin was obviously drawn tothe figure of Noor, and describes this novel as a 'tribute' to her. I must admit I did struggle a little with Noor's encounters with the fairies, which sat rather oddly in an otherwise bitterly realist story, though it does chime with her parallel career as a children's writer. But overall Never Forget You is absorbing and moving, and it definitely sent me down a rabbit hole of spies and resistance fighters.

17.10.22

The Twelfth Day of July

When venerable children's and young adult author Joan Lingard died earlier this year, I realised to my dismay that I had never read any of her work. A quick search on Brotherhood Books turned up The Twelfth Day of July, from 1970, the first in a series of five books about a young Belfast couple, one Catholic and one Protestant, who meet and (I guess, in later books?) fall in love across the sectarian divide.

In The Twelfth Day of July, Kevin and Sadie are young teens who become caught up in an escalating series of dares, raids into each other's territory, in the lead-up to the Protestants' big celebration and march on the 12th July. With their friends and siblings egging them on, they daub paint on enemy walls, break into each other's houses, hide out in enemy backyards, and confront each other in the streets to hurl insults, and finally, fists.

The structure of this slim book is deceptively simple, a fable of provocation and gradually escalating violence where the protagonists also slowly develop a growing respect and admiration for each other's guts and daring, ending in a satisfying truce where both sides boycott the 'Twelfth' for a day at the seaside, in neutral territory, just hanging out as young people together.

I'd be interested to see how the story develops across the next four books. The Twelfth Day of July is an engaging introduction to the Belfast Troubles, with quite low stakes at this stage, though I'm sure as the series progresses things will become more serious. It's hard to believe this book is over 50 years old -- though the period detail has dated, the characters and action are as fresh and lively as anything written today.

14.10.22

The Castle on the Hill

This is another Coronet edition with a terrible cover -- absolutely no idea who these two are supposed to be. The woman has to be Miss Brown, she's not young or pretty or blonde enough to be Prunella. But who is the bloke? Presumably Jo Isaacson? But their whole pose is wrong, and oh my god, the hat and stripy shirt, the white suit, not to mention the woman's wraparound skirt and flowery blouse -- did I mention this book is set in 1940?? I despair!

The Castle on the Hill was published in 1942 and set a couple of years before, in the darkest days of the early war, Dunkirk and the Blitz, and I think this accounts for the slightly breathless tone in which it's written. It swerves uncomfortably close to being pure wartime propaganda, and it pulls too many of its punches to be really successful. The young pacifist finds an 'out' by performing courageous ambulance service in London; when a young woman becomes pregnant out of wedlock, the baby conveniently dies. There are pompous patriotic speeches and lyrical descriptions of 'this England' which 'we're' fighting for. For a Goudge novel, there is a surprisingly high body count, but hey, that's war I guess. I did enjoy the slightly more subtle spiritual thread that weaves through several characters and the thorn tree in the wood, and even that is not really that subtle!

I'm glad to add The Castle on the Hill to my collection but I don't think I'll revisit it as often as the Torminster books or the books about the Eliot family.

11.10.22

The Believer

Sarah Krasnostein is an incredible writer, and her previous book, The Trauma Cleaner, won just about every award it was eligible for. The Believer is a more diffuse project than Trauma Cleaner, but it's just as wonderful to read and ponder. Trauma Cleaner was focused on one woman's extraordinary life story; The Believer encounters six different individuals or groups, who all have one thing in common -- they all have faith in something. Krasnostein spends time with a 'death doula' and one of her clients at the very end of life; a group investigating paranormal phenomena; some creationists; a woman who spent 35 years in jail after killing her abusive husband (it was quite startling to come across this story so soon after reading The Mother, but it was a total coincidence...); a family of Mennonites; and believers in UFOs.

The UFO section centres on the disappearance of Frederick Valentich, a 20 year old pilot who vanished over Bass Strait but reported seeing mysterious lights and an inexplicable craft moving above him before he went missing. My father was also based at Moorabin Airport at the time, and I can remember discussions about this incident in my childhood; Dad always believed that Valentich was unknowingly flying upside down.

In every encounter, even where Krasnostein seems completely sceptical about her subjects' beliefs (particularly with the Mennonites and the creationists), her gentle but rigorous attention is notable. She is motivated by a desire to understand, not to judge, and even where it's impossible for her to see any way across the divide, she tries her utmost to reach out a hand. In these days when we are all so quick to pronounce and condemn, this book is a salutary corrrective. The Believer may not provide the most scholarly or coherent narrative, but it's definitely a fascinating and absorbing journey.

9.10.22

The Mother

The Mother is a terrific, informative, gripping and chilling novel which held me enthralled to the final page. I'd heard good things about this book and there was a long reserve list at the library, which is usually a good sign, but The Mother exceeded expectations.

It's a fantastic premise for a story. Miriam is a middle aged mother who is at first thrilled that her adult daughter has settled down at last with such an attentive partner. He's romantic, thoughtful, a loving father. And yet there are subtle hints that all is not well. Why install a security system that points at the front door? Why discourage Miriam from visiting to help with the babies? Gradually, to her horror, Miriam learns just how toxic Ally's marriage really is, and that's where the tension really ramps up.

I do seem to have been reading an awful lot of books about violence against women lately, but The Mother is a cracker. The dawning realisation that Miriam and Ally are totally helpless against Ally's husband is totally chilling and, unfortunately, absolutely realistic. Caro has obviously done her research, and while the police are sympathetic to Miriam and Ally, the legal system is stacked against them. Miriam ultimately decides to take drastic action, and she is not excused from the consequences of that decision.

Caro acknowledges Jess Hill's See What You Made Me Do both within the novel and in the author's notes, and I would bet that The Mother will reach an even wider audience than Hill's outstanding work. Let's hope it helps.

7.10.22

Circe

Madeline Miller's Circe was recommended by my book group ladies, and I reserved it from the library on the spot. I ended up reading most of it in the Glen Waverley library, waiting for my husband's eye surgery to finish, and it transported me far, far away, in space and time, to the Ancient Greek Age of Heroes.

I knew Circe vaguely as the sorceress who turned Odysseus' sailors into swine, but Miller's novel does a magnificent job of filling out her back story and incorporating the other aspects of her legend: daughter of Helios, the Sun; magic worker; spurned lover, creator of her own craft and happiness; mother of potions and herbal magic. This novel is beautifully written, vivid, absorbing.

Circe is one of the most enjoyable adult novels I've read this year, and a perfect way to while away a five hour wait.

5.10.22

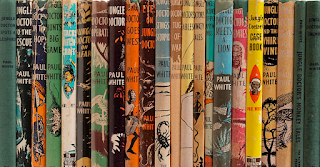

Jungle Doctor Attacks Witchcraft

I read loads of these as a child, though I didn't remember much about them, and the spines jumped off the shelf at me when I came across them in City Basement Books a few weeks ago. For the sake of my childhood, I selected just one, Jungle Doctor Attacks Witchcraft, and expected it to be hideously racist. It was certainly patronising, but it wasn't too bad on the racism scale. What I'd totally forgotten was the heavy-handed Christian messaging -- every case who crosses Jungle Doctor's path (he is ever named, except as 'Bwana') can be turned into a parable, usually delivered not by Bwana himself, but by his African sidekick Daudi (who seems to do a lot of the leg work around the mission station).

"H-e-e-e-e," said Daudi, "you may pull out the plant, but you cannot get rid of the results of it. Behold, indeed, this plant is like sin. You may do your best to destroy it, but you cannot get away from its effects. The Bible says truly: 'The soul that sinneth it shall die.'"

The books are short, just over a hundred pages, and generously illustrated (the illustrations are pretty racist, so I won't reproduce one here). I guess as a child I could see a few parallels between Jungle Doctor's life in Tanganika Territory (now Tanzania) and our lives in Papua New Guinea; and the evangelical content was similar to what I was imbibing every day from our neighbours, my friends at school and their missionary parents. Another trip down memory lane, but this time it's not one I'm eager to repeat.

2.10.22

Nowhere To Hide

It's hard to believe that six years have passed since that glorious day in 2016 when the Western Bulldogs won the AFL Premiership for the first time in 62 years. Tom Boyd was an integral part of that victory, playing perhaps the best game of his life, scoring three goals, including the breathtaking kick that sealed the game and resulted in this iconic image, with teammate Toby McLean jumping on his back, the very personification of joy and triumph:

|

| Image: Fox Sports |

Bulldogs supporters claim that in that single moment, Tom Boyd justified his enormous contract, at the time the biggest ever awarded to a player -- he was worth every penny. But that moment, and the huge contract deal, came at a tremendous personal cost to Boyd. Nowhere To Hide is the story of his football career, and more importantly, his personal journey through hell and out the other side.

Reading this book, combined with the recent appalling allegations of racism emerging from Hawthorn, and the long and sorry history of racism, misogyny and other scandals, have done a lot to put me off the whole sport of football. Correction, it's not a sport -- it's an industry. And like any business where there is far too much money sloshing around, common decency toward individuals, let alone empathy and compassion, seem to get lost in the mix.

On the surface, Tom Boyd seemed to have it all -- a young, white, privileged male, gifted with athletic talent, smart, articulate, good-looking, a number one draft pick -- surely he was living the dream? And he copped a huge amount of abuse for this very reason. If anything went wrong, he felt ungrateful, and he felt the pressure of everyone's expectations. When it sunk in for me that when he made the decision to leave GWS to come to the Western Bulldogs, he was younger than my daughter is now, I was horrified. He was a twenty year old kid, prone to injury, suffering from anxiety and insomnia, not sure who to trust, reluctant to admit he was struggling, because he felt as if he was letting everyone down.

After reading Nowhere To Hide, I don't think I will ever voice a criticism of a footballer again, even in the privacy of my own living room. I feel ashamed of the casual insults I've voiced aloud, telling myself it's all part of the theatre of the game. No, these are vulnerable young men, many of them just kids, trying their hardest, and suffering demons in their heads that we know nothing about. Shame on us all.

30.9.22

Freedom Ride

Sue Lawson's Freedom Ride somehow slipped by me when it was first published -- oh, wait, it was 2015, I did have a lot going on that year... This was another book recommended by a school librarian, one she believed every student should read. I would add that every Australian adult should read it, too. Freedom Ride focuses on a shameful part of our recent history that some people would prefer remained forgotten or swept beneath the rug.

Despite the title, Freedom Ride is centred less on the 1960s freedom rides themselves than on one of the country towns they visited. The very first chapter is confronting for a modern reader, as an Aboriginal women is kept waiting in a grocery store until all the white customers are served -- and almost worse, when one white man insists on her being served before him, another customer is loudly affronted. The battle lines are clearly drawn along racial lines, and teenage Robbie has to examine his own attitudes when he befriends caravan park owner Barry, who has returned from London with a more enlightened philosophy.

There is another drama playing out in Robbie's family, when he discovers that his horrible father and grandmother have to been lying to him for most of his life, but the racial politics is revolting. There are 'colour bars' in place in the local shops, the theatre, the swimming pool -- it's pretty much apartheid. The indigenous population are relegated to neglected shanty towns on the fringes of (fictional) Walgaree, and then blamed for their own disadvantage. So when Barry hires Aboriginal boy Micky as well as Robbie to help out in the caravan park, all hell breaks loose.

Freedom Ride is involving and engaging, but in another way, it's hard to read. It's set in the year before I was born, before the referendum that gave Aboriginal people citizenship. It still shocks me that this happened within my own lifetime, and that we still have so very far to go.

28.9.22

A City of Bells

A City of Bells was one of the four Elizabeth Goudge novels I pounced on in a second hand bookshop with a cry of delight a few weeks ago -- all Coronet editions from the 1970s, all with terrible covers. You would think from this image that it's a time travel story, as the woman is all decked out in Edwardian gear but the man is pure 1970s Mills & Boon. Presumably they are supposed to be Felicity and Jocelyn, though neither of them appear as described in the book: Felicity is supposed to have short golden hair, for one thing (admittedly quite unusual in Edwardian England, but whatever...)

As I began re-reading A City of Bells, it seemed more and more familiar. I think this was a novel that I read many times in high school, and it was comfort reading even then. The scenes in peaceful Torminster, Jocelyn's bookshop, and the characters of the children, were especially vivid -- the parts in London and the theatre, and the transformation of Ferranti's poem into a play, all seem a bit contrived to me now. Goudge is pretty hopeless at romantic/sexual love, and she can be sentimental. But City of Bells is an early work, so I'm prepared to forgive its flaws! And I love pale, sensitive Henrietta, and her adopted brother, the boisterous Hugh Anthony, and the saintly figure of Grandfather, the Canon. (One day I must sit down and work out all the gradations of the Anglican offices, because it's all very confusing.)

A lovely, nostalgic trip down a very English memory lane.

26.9.22

Rattled

I seem to be reading a lot of books about violence against women at the moment -- maybe there are just a lot more of them coming out at the moment. I raced through Ellis Gunn's account of her experience of being stalked -- it's extremely pacy and readable. Rattled is perhaps less scholarly than some books on this subject, but gripping in its use of anecdote and almost poetic summaries at the end of each chapter which really drive the reality of women's experience home.

Some might say Gunn was 'lucky' in that her stalker ('The Man') never physically attacked her, and eventually gave up his pursuit, but his stalking shattered her life for many months, making her terrified to leave her house, terrified to stay home alone, terrified to visit her usual haunts, terrified to travel anywhere new. But perhaps even more confronting than her account of the ordeal The Man inflicted on her is Gunn's almost casual recounting of other incidents in her life when she encountered or witnessed male violence: from an abusive marriage to seeing an elderly man on a train trying to persuade a young lone backpacker to come and stay at his house. Haven't all our lives been filled with incidents like these? Haven't we all, even if we haven't experienced violence ourselves, at least felt the feather's touch of the 'lucky escape,' or shuddered at a friend's story? And yet for so long we've shrugged off this behaviour as being just the way the world is. Perhaps things are finally shifting -- but alas, experience teaches us that any ground gained will probably be followed by an even worse backlash.

Watch this space.

23.9.22

Our Crooked Hearts

I particularly enjoyed the mother-daughter dynamic, which started out all grumpy-daughter-complains-that-her-mum-doesn't-understand-her, but ended up being really painful and poignant as the reasons behind that estrangement were gradually revealed and resolved. The magic was thoroughly grounded and -- I want to say realistic? Sometimes magic in fantasy can be a bit wifty-wafty, but this felt gritty and edgy. The supportive men characters were another unexpected bonus in a book dominated by women's power, and women's friendship.

Our Crooked Hearts is a really terrific read.

21.9.22

Bedtime Story

There was a massive reserve queue for Chloe Hooper's Bedtime Story -- I think I was about 38th in line (there are 27 waiting now). This is why we need PLR and ELR, people... So when I finally got my mitts on it, I probably raced through it more quickly than it deserves, conscious of all those future readers breathing impatiently down my neck.

This is a book to be savoured and treasured. Beautifully produced, with abstract illustrations by Anna Walker, Bedtime Story is a memoir about one family, struck by the lightning bolt of a cancer diagnosis, and Hooper's desperate flailing to find the right way to tell her young children: the perfect picture book, the perfect children's novel, the perfect words. Of course there are no perfect words (though she gratefully admits that some come close) and the search through children's literature becomes a framing device through which to explore the impact that this devastating news has on the entire family, and the different ways they find to cope and keep on going.

I had forgotten that Chloe Hooper was married to the incomparable Don Watson; when I realised who her husband was, it sent me, heart in mouth, to search the internet for updates on his health. Some sections of this book might be too harrowing for some, but it is a gorgeously written, thoughtful meditation on mortality, crisis, childhood, love and family which richly deserves its long reserve queue.