What a beautiful novel. Also borrowed from my friend Christine, this is the first time I've read Georgia Blain's writing. I was aware of the tragic irony of her story, that she'd just finished writing a novel about a woman dying of a brain tumour when she was diagnosed herself with the same kind of aggressive, incurable tumour (incidentally, the same glioblastoma that killed my friend Sandra). Knowing this, I was wary of approaching Between A Wolf and A Dog, but I needn't have worried.

I wasn't familiar with the expression 'between a wolf and a dog' (it's French) but it refers to the hour of twilight when apparently it's difficult to distinguish between those two animals. The whole novel is like this: strong but delicately poised, at once tender and steely. It takes place over a single rainy Sydney day, following Hilary as she contemplates her illness and the decision she's taken; her daughters April, a singer, and Ester, a therapist, estranged over the infidelity of April and Ester's pollster husband Lawrence. The narrative dips back to happier and also more fraught times, and Ester's patients introduce vignettes of lost love, loneliness and pain.

This was the kind of novel I aspired to achieve when I first began writing -- acute psychological insight married to beautiful, sparse, lyrical prose. I never quite got there, and discovered my strengths lay elsewhere (to put it kindly). What a terrible loss is Georgia Blain, but how fortunate we are that she was with us long enough to produce superb work like this.

30.11.19

27.11.19

The Woman Who Cracked the Anxiety Code

The Woman Who Cracked the Anxiety Code was Dr Claire Weekes, an Australian doctor who wrote self-help books about anxiety and panic attacks which sold millions of copies all over the world, and still sell well today. Yet I had never heard of her!

Judith Hoare's biography is sub-titled The Extraordinary Life of Dr Claire Weekes and in many ways Weekes' life was indeed extraordinary. She was a scientific researcher in the 1920s, when women were barely admitted to university, and her pioneering work on lizard reproduction is still cited today. She reinvented herself several times, planning a musical career, then an upmarket travel agency. The latter plan being kiboshed by the outbreak of WWII, she went back to university and qualified as a GP. Then, in the 1960s and beyond, came the self-help books.

This is where her story, sadly, becomes less extraordinary. Being a woman, and a mere general practitioner rather than a psychiatrist, writing for a popular audience (so she could actually help as many people as possible) rather than in academic journals or psychiatric forums, her work was belittled and overlooked. And yet her mantra (based on both scientific knowledge and personal experience) -- Face, Accept, Float, Let Time Pass -- presaged modern approaches to dealing with anxiety like CBT and ACT. Her key insight was not to fight the feelings of panic, but to let them wash through you, and to "float" through them.

I would have liked a little more on her work, which was sometimes presented in a slightly confusing way by Hoare, but overall this was a fascinating introduction to a woman who should be more widely known. Borrowed from my friend Christine.

Judith Hoare's biography is sub-titled The Extraordinary Life of Dr Claire Weekes and in many ways Weekes' life was indeed extraordinary. She was a scientific researcher in the 1920s, when women were barely admitted to university, and her pioneering work on lizard reproduction is still cited today. She reinvented herself several times, planning a musical career, then an upmarket travel agency. The latter plan being kiboshed by the outbreak of WWII, she went back to university and qualified as a GP. Then, in the 1960s and beyond, came the self-help books.

This is where her story, sadly, becomes less extraordinary. Being a woman, and a mere general practitioner rather than a psychiatrist, writing for a popular audience (so she could actually help as many people as possible) rather than in academic journals or psychiatric forums, her work was belittled and overlooked. And yet her mantra (based on both scientific knowledge and personal experience) -- Face, Accept, Float, Let Time Pass -- presaged modern approaches to dealing with anxiety like CBT and ACT. Her key insight was not to fight the feelings of panic, but to let them wash through you, and to "float" through them.

I would have liked a little more on her work, which was sometimes presented in a slightly confusing way by Hoare, but overall this was a fascinating introduction to a woman who should be more widely known. Borrowed from my friend Christine.

Labels:

Australian women writers,

biography,

book response,

psychology

23.11.19

When the Lyrebird Calls

I'm not sure if this is the first time I've found myself reading three books at the same time, all by Australian women writers.

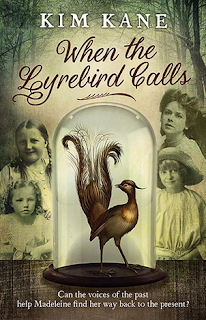

I've been meaning to read Kim Kane's time slip novel, When the Lyrebird Calls, since it first came out, and I found this copy at Brown & Bunting. My ladies' book group thought highly of it, but someone said, what a shame the cover is so drab.

Having read the book, I think the designer (ooh, I just discovered it's Debra Billson, who has produced a gorgeous design for my forthcoming middle-grade book, The January Stars) has done an amazing job of tracking down contemporary photographs that resemble the four girls in the story. And, spookily, yesterday I happened to look up that first classic Australian time-slip novel, Ruth Park's Playing Beatie Bow, and noticed the original Puffin edition cover:

As Kim Kane makes a point of referencing Beatie Bow in her acknowledgements, the similarity in these covers can't be a coincidence. But I'm not sure how many readers, especially young readers, would pick up on the homage, particularly as it eluded a bunch of highly experienced school librarians and children's literature enthusiasts (shame on us).

Aanyway, I wasn't sure I was going to enjoy this book when it opened with a scene of three young girls destroying a fancy doll. I have a tendency to feel sorry for inanimate objects and this overt cruelty didn't endear the young protagonists to me. But once the time slip happened, I was all in. Madeleine doesn't travel back and forth but stays in 1900 for an extended period, which gives a good solid look at the issues of the time (Federation, suffrage, racism, spiritualism) as well as the tangled family dynamics of the Williamson household where Madeleine ends up. (Extra points to Gertie for attending my alma mater, PLC!) It's not till the final chapter, back in her own time, that Madeleine discovers some family secrets that make sense of what she's seen.

Kim Kane has a quirky and often humorous turn of phrase that adds to the enjoyment, and I appreciated the feminist emphasis as well as the sensitive portrayal of a young Aboriginal man (he deserves his own book, I reckon). Loved it!

I've been meaning to read Kim Kane's time slip novel, When the Lyrebird Calls, since it first came out, and I found this copy at Brown & Bunting. My ladies' book group thought highly of it, but someone said, what a shame the cover is so drab.

Having read the book, I think the designer (ooh, I just discovered it's Debra Billson, who has produced a gorgeous design for my forthcoming middle-grade book, The January Stars) has done an amazing job of tracking down contemporary photographs that resemble the four girls in the story. And, spookily, yesterday I happened to look up that first classic Australian time-slip novel, Ruth Park's Playing Beatie Bow, and noticed the original Puffin edition cover:

As Kim Kane makes a point of referencing Beatie Bow in her acknowledgements, the similarity in these covers can't be a coincidence. But I'm not sure how many readers, especially young readers, would pick up on the homage, particularly as it eluded a bunch of highly experienced school librarians and children's literature enthusiasts (shame on us).

Aanyway, I wasn't sure I was going to enjoy this book when it opened with a scene of three young girls destroying a fancy doll. I have a tendency to feel sorry for inanimate objects and this overt cruelty didn't endear the young protagonists to me. But once the time slip happened, I was all in. Madeleine doesn't travel back and forth but stays in 1900 for an extended period, which gives a good solid look at the issues of the time (Federation, suffrage, racism, spiritualism) as well as the tangled family dynamics of the Williamson household where Madeleine ends up. (Extra points to Gertie for attending my alma mater, PLC!) It's not till the final chapter, back in her own time, that Madeleine discovers some family secrets that make sense of what she's seen.

Kim Kane has a quirky and often humorous turn of phrase that adds to the enjoyment, and I appreciated the feminist emphasis as well as the sensitive portrayal of a young Aboriginal man (he deserves his own book, I reckon). Loved it!

20.11.19

Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine

I picked up my copy of Gail Honeyman's smash hit, Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine, from Royal Talbot Rehabilitation Hospital's second hand book shelves earlier this year. My copy is plastered with even more award stickers than the one in the picture, and after reading it, it's easy to see how it's amassed so many accolades.

This is a mystery story, in some ways a horror story, but packaged up in highly entertaining wrapping. Eleanor Oliphant tells her own story, and her voice is fresh, funny and very distinctive, even while she's recounting a story of pain, loneliness and childhood abuse that might be impossible to digest otherwise. At times the reader almost feels guilty for finding Eleanor amusing, as she is clearly dealing with a legacy of tremendous suffering.

As always, salvation lies in connection. Through small acts of kindness, Eleanor re-enters the world she has shut out, and it's rewarding to journey with her, as bit by bit, she blossoms. She is supposed to be about thirty, but sometimes she reads like a woman twice that age. A bonus is that the book is set in Glasgow and lovely Scottishness lies over the whole book like a mist. An excellent pick-up.

This is a mystery story, in some ways a horror story, but packaged up in highly entertaining wrapping. Eleanor Oliphant tells her own story, and her voice is fresh, funny and very distinctive, even while she's recounting a story of pain, loneliness and childhood abuse that might be impossible to digest otherwise. At times the reader almost feels guilty for finding Eleanor amusing, as she is clearly dealing with a legacy of tremendous suffering.

As always, salvation lies in connection. Through small acts of kindness, Eleanor re-enters the world she has shut out, and it's rewarding to journey with her, as bit by bit, she blossoms. She is supposed to be about thirty, but sometimes she reads like a woman twice that age. A bonus is that the book is set in Glasgow and lovely Scottishness lies over the whole book like a mist. An excellent pick-up.

16.11.19

Through the Language Glass

The younger daughter begged me to order Guy Deutscher's Through the Language Glass for her, prompted by Stephen Fry's fulsome endorsement (see above: 'jaw-droppingly wonderful' and 'left me breathless and dizzy with delight').

Well, suffice to say that both the daughter and I felt that Stephen Fry had gone a little overboard with his praise this time. She slogged through it first, heroically sticking to her routine of one chapter per night (the chapters are quite long), then handed it to me. That was months ago, but I've finally managed to push through to the end.

This is not a terrible book, by any means. The subject matter is fascinating (how does the language we speak influence our perception of the world?) and Deutscher does his best to jolly us along with linguistic humour. But it's a thorough (some may say, too thorough) survey of a quite dry academic field, and its conclusions are fairly underwhelming, to wit, yes, language does influence some aspects of how we perceive the world, but not much, and only in certain areas (colour, gender, spatial orientation).

Probably the most interesting section dealt with one Australian Aboriginal language (Guugu Yimithirr) which requires its speakers to take note of the compass directions whenever they describe the position of something. So instead of saying, 'there is an ant to the right of my foot,' they would say, 'there is an ant to the south-west of my foot.' This means they are constantly, unconsciously orienting themselves geographically in their surroundings. That would be a handy skill to have.

Well, suffice to say that both the daughter and I felt that Stephen Fry had gone a little overboard with his praise this time. She slogged through it first, heroically sticking to her routine of one chapter per night (the chapters are quite long), then handed it to me. That was months ago, but I've finally managed to push through to the end.

This is not a terrible book, by any means. The subject matter is fascinating (how does the language we speak influence our perception of the world?) and Deutscher does his best to jolly us along with linguistic humour. But it's a thorough (some may say, too thorough) survey of a quite dry academic field, and its conclusions are fairly underwhelming, to wit, yes, language does influence some aspects of how we perceive the world, but not much, and only in certain areas (colour, gender, spatial orientation).

Probably the most interesting section dealt with one Australian Aboriginal language (Guugu Yimithirr) which requires its speakers to take note of the compass directions whenever they describe the position of something. So instead of saying, 'there is an ant to the right of my foot,' they would say, 'there is an ant to the south-west of my foot.' This means they are constantly, unconsciously orienting themselves geographically in their surroundings. That would be a handy skill to have.

13.11.19

Sick Bay

Holding Nova Weetman's latest junior fiction novel, Sick Bay, in my hands was a bittersweet experience. The cover of Sick Bay was the last published artwork by my dear friend Sandra Eterovic before she died, almost exactly a year ago, of brain cancer. (And yes, the awful irony of the title is not lost on me.) There is a lovely tribute to Sandra from Nova Weetman in the acknowledgments; Sandra had also supplied the cover artwork for Weetman's previous two books.

Sick Bay is a story of friendship. Riley has diabetes, but dealing with her anxiously controlling mother is a bigger problem than her health. Meg takes refuge in Sick Bay when life becomes too hard -- her father has died and her mother has sunk into a deep depression. Compounding the girls' personal problems is the landscape of friendship at school with one girl, Lina, who dispenses and withholds her approval like a weapon.

Come to think of it, Sick Bay is really about control -- the things you can control and the things you can't. Riley is struggling to take control of her own diabetes management, while Meg is powerless to help her mother. These are Grade 6 pupils, with high school on the horizon, and the world is about to get bigger and even harder to navigate. Nova Weetman writes so beautifully about friendship and family and the blindsides of mental health. Perhaps it's appropriate that this was the last cover from Sandra before we lost her.

Sick Bay is a story of friendship. Riley has diabetes, but dealing with her anxiously controlling mother is a bigger problem than her health. Meg takes refuge in Sick Bay when life becomes too hard -- her father has died and her mother has sunk into a deep depression. Compounding the girls' personal problems is the landscape of friendship at school with one girl, Lina, who dispenses and withholds her approval like a weapon.

Come to think of it, Sick Bay is really about control -- the things you can control and the things you can't. Riley is struggling to take control of her own diabetes management, while Meg is powerless to help her mother. These are Grade 6 pupils, with high school on the horizon, and the world is about to get bigger and even harder to navigate. Nova Weetman writes so beautifully about friendship and family and the blindsides of mental health. Perhaps it's appropriate that this was the last cover from Sandra before we lost her.

6.11.19

On Writing

I should confess at the outset that I haven't read much -- or any, really -- of Stephen King's works, though of course I recognise what a hugely successful author he is. His subject matter, often shading into horror, is not my cup of tea.

But he certainly knows what he's talking about when it comes to the subject of writing itself, and this slim volume On Writing has terrific, pithy and straightforward advice about the craft, as well as including an interesting autobiographical section and an equally interesting account of the road accident that nearly killed him while he was writing it.

He has paid his dues, beginning his writing career while holding down a hideous job in a commercial laundry and living with his young family in a trailer, tapping out his first books on his knees. So he's earned his success and I don't begrudge it to him.

But Stephen. Come on. He describes his current working day: mornings, writing with the door shut to prevent interruptions until you reach your daily target (for him, 2,000 words; lesser mortals might aim for 1,000). Afternoons: naps and letters. Evenings: hanging out with the family, walking, reading. That sounds, frankly, idyllic.

When do you do the housework, Stephen? When do you make the lunches and dinner for everyone and do the grocery shopping? When do you drive your mum to the doctor and your anxious teenager to school? When do you clean out the rabbit and vacuum the floors? When do you hang on the phone to Centrelink to sort out the finances of your disabled sibling? How do you shoehorn all that in, Stephen? Or is there someone in the background taking care of all that?

To be fair, he is generous with his acknowledgement of his wife Tabby's help and encouragement along the way, and I have no doubt that he works hard at his job. But wow, wouldn't it be nice to be able to shut that door in the morning and never be interrupted.

But he certainly knows what he's talking about when it comes to the subject of writing itself, and this slim volume On Writing has terrific, pithy and straightforward advice about the craft, as well as including an interesting autobiographical section and an equally interesting account of the road accident that nearly killed him while he was writing it.

He has paid his dues, beginning his writing career while holding down a hideous job in a commercial laundry and living with his young family in a trailer, tapping out his first books on his knees. So he's earned his success and I don't begrudge it to him.

But Stephen. Come on. He describes his current working day: mornings, writing with the door shut to prevent interruptions until you reach your daily target (for him, 2,000 words; lesser mortals might aim for 1,000). Afternoons: naps and letters. Evenings: hanging out with the family, walking, reading. That sounds, frankly, idyllic.

When do you do the housework, Stephen? When do you make the lunches and dinner for everyone and do the grocery shopping? When do you drive your mum to the doctor and your anxious teenager to school? When do you clean out the rabbit and vacuum the floors? When do you hang on the phone to Centrelink to sort out the finances of your disabled sibling? How do you shoehorn all that in, Stephen? Or is there someone in the background taking care of all that?

To be fair, he is generous with his acknowledgement of his wife Tabby's help and encouragement along the way, and I have no doubt that he works hard at his job. But wow, wouldn't it be nice to be able to shut that door in the morning and never be interrupted.

Labels:

book response,

non-fiction,

writing,

writing habits

4.11.19

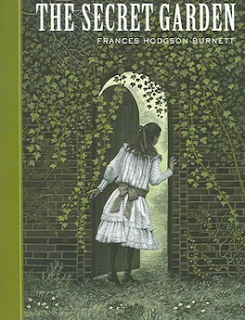

The Secret Garden

I first read my mother's copy of The Secret Garden from 1949, which I still own, very battered round the edges now. It was her favourite childhood book, and it's probably my all-time favourite, too (in a very crowded field).

The Secret Garden, published by Frances Hodgson Burnett in 1911, was somewhat overlooked in her lifetime, and wasn't even mentioned in her obituary. The sweet Cinderella story of A Little Princess and the ghastly Little Lord Fauntleroy were praised, but no one thought much of The Secret Garden. These days it's regarded as a classic, a masterpiece.

I love so much about this book. The notion of a secret, hidden, neglected garden, closed in by high walls and a locked door, is deliciously enticing. I love sour, lonely Mary Lennox; sturdy Dickon who communes with the wild animals; and fretful, sickly Colin. The scene where Mary and Colin scream at each other in a furious fight in the middle of the night used to give me such a thrill. And all the while, spring is creeping over the moor and reaching into the children's garden, healing their bodies and their minds.

It's been a few years since I last read The Secret Garden, and this time it was the mental health angle that jumped out at me. Neglected, unloved Mary is isolated and angry with the world; poor 'spoiled' Colin is actually tormented with anxiety; and his father, Mr Craven, is sunk in a deep depression after his wife's death. It's communion with nature, fresh air and sunshine and exercise, and a meaningful project in bringing the garden back to life, as well as connecting with each other, that brings them all back to health and happiness. It's a very simple story, but it's the very simplicity of the message that carries such power.

The Secret Garden, published by Frances Hodgson Burnett in 1911, was somewhat overlooked in her lifetime, and wasn't even mentioned in her obituary. The sweet Cinderella story of A Little Princess and the ghastly Little Lord Fauntleroy were praised, but no one thought much of The Secret Garden. These days it's regarded as a classic, a masterpiece.

I love so much about this book. The notion of a secret, hidden, neglected garden, closed in by high walls and a locked door, is deliciously enticing. I love sour, lonely Mary Lennox; sturdy Dickon who communes with the wild animals; and fretful, sickly Colin. The scene where Mary and Colin scream at each other in a furious fight in the middle of the night used to give me such a thrill. And all the while, spring is creeping over the moor and reaching into the children's garden, healing their bodies and their minds.

It's been a few years since I last read The Secret Garden, and this time it was the mental health angle that jumped out at me. Neglected, unloved Mary is isolated and angry with the world; poor 'spoiled' Colin is actually tormented with anxiety; and his father, Mr Craven, is sunk in a deep depression after his wife's death. It's communion with nature, fresh air and sunshine and exercise, and a meaningful project in bringing the garden back to life, as well as connecting with each other, that brings them all back to health and happiness. It's a very simple story, but it's the very simplicity of the message that carries such power.

Labels:

antique fiction,

book response,

garden,

re-reading

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)