I remember being pleased but slightly bemused when Ballet Shoes scored a shout-out during the 1998 Meg Ryan-Tom Hanks rom-com, You've Got Mail. Ryan, a bookshop owner, recommended Ballet Shoes to a customer, but mentioned that there was a whole series of other 'Shoes' book as well. Er, what?

It wasn't till much later that I realised that a number of Streatfeild books had been re-titled to create a 'series' where none had originally been intended. Thus Curtain Up! became Theatre Shoes, White Boots became Skating Shoes, The Circus Is Coming became Circus Shoes etc. The Painted Garden became, ridiculously, Movie Shoes. (Tennis Shoes was always Tennis Shoes.) Blerch. What even are Movie Shoes, or Theatre Shoes, supposed to be, anyway? (Though I have to admit that if you google 'theatre shoes', the internet summons... shoes.)

So, I have read Theatre Shoes before, but under its old moniker of Curtain Up! I didn't remember much about it, except for the name Sorrel, which I think is gorgeous. It's war-time and the three Forbes children, unknowingly part of a famous theatrical family, are sent to Madame Fidolia's famous stage school where the Fossil sisters had gone before them. There's another tiny cameo for the Fossils, who are all overseas or flying planes, but provide scholarships for the Forbes siblings. Sorrel discovers that she wants to be an actress, Mark really wants to be a sailor but can endure acting and singing if he's allowed to 'pretend' himself into a role, and the youngest Holly turns out to be a gifted comic.

In this book, it's the details of wartime privation that are the most striking -- the shops are all empty, Grandmother's grand furniture has been sold to make ends meet, the children long for smart attache cases and lovely clothes, but have to make do with 'utility frocks.' (I had never heard of these, but came across them again in Domestic Soldiers, of which more presently.) The extended family are beautifully sketched -- Grandmother, the egotistical matriarch, kind uncles and aunts, and Uncle Francis who is a bombastic Shakespearean Ac-Tor, as well as the children's cousins, supremely self-confident Miranda and funny Miriam. Annoyingly, there is one rather racist scene where a wounded Chinese sailor speaks pidgin English to Sorrel.

The obligatory Grand-Nanny role in this book is filled by Hannah, who had been housekeeper to the children's late grandfather, but is assumed by everyone (including herself) to inherit, without question, the job of looking after the children. This means moving to London and living in a very run-down house, sharing a bedroom with Holly and (horrors) riding escalators. I couldn't help wondering if poor Hannah might have had somewhere else she would rather have been.

24.12.19

21.12.19

The Fear of Child Sexuality

The Fear of Child Sexuality: Young People, Sex and Agency is not the sort of title you are accustomed to seeing on this blog, gentle reader. It's been a long time since I read an academic work (which this is) and to be honest, I wouldn't have come across it if Steven Angelides didn't happen to be an old friend.

Reading academic books exercises different muscles in the brain. I'll admit that I found this a difficult text to grapple with; sometimes I could barely understand it, though most of the time I think I had a foggy idea. Here goes.

The issue of child (more accurately here, adolescent) sexuality is a vexed one in anglophone societies at the moment. Angelides examines a number of case studies of 'sex panics' centred on young people's sexual knowledge and expression -- sex education; the scandal around Bill Henson's photographs of pubescent youths; laws around sexting which can see young people themselves branded as sex offenders even when the activity has been fully consensual; relationships between teachers and students. Broadly speaking, he argues that in the rush to protect young people from the consequences of 'premature' exposure to sexual knowledge or activity, we erase their own desires, awareness and ability to act. Adolescents don't magically become sexual beings overnight when they reach the age of consent -- and that age can vary depending upon the activity and the parties involved. Yes, of course it is important to shield young people from abuse. But it's not alway so easy to decide what is abusive behaviour, and what harm might result. Young people need more information about sex, not less.

Steven has been the target of some unfounded attacks as the result of writing this book. It's a controversial topic but his approach is thoughtful and nuanced. I found it extremely interesting, and it gave me lots to think about.

Reading academic books exercises different muscles in the brain. I'll admit that I found this a difficult text to grapple with; sometimes I could barely understand it, though most of the time I think I had a foggy idea. Here goes.

The issue of child (more accurately here, adolescent) sexuality is a vexed one in anglophone societies at the moment. Angelides examines a number of case studies of 'sex panics' centred on young people's sexual knowledge and expression -- sex education; the scandal around Bill Henson's photographs of pubescent youths; laws around sexting which can see young people themselves branded as sex offenders even when the activity has been fully consensual; relationships between teachers and students. Broadly speaking, he argues that in the rush to protect young people from the consequences of 'premature' exposure to sexual knowledge or activity, we erase their own desires, awareness and ability to act. Adolescents don't magically become sexual beings overnight when they reach the age of consent -- and that age can vary depending upon the activity and the parties involved. Yes, of course it is important to shield young people from abuse. But it's not alway so easy to decide what is abusive behaviour, and what harm might result. Young people need more information about sex, not less.

Steven has been the target of some unfounded attacks as the result of writing this book. It's a controversial topic but his approach is thoughtful and nuanced. I found it extremely interesting, and it gave me lots to think about.

19.12.19

Helicopter Man

Elizabeth Fensham's debut novel Helicopter Man won the CBCA Book of the Year for Younger Readers in 2006. Like The Wych Elm, it revolves around perceptions of reality and memory.

Pete and his dad are on the run. Pete's diary offers us an entertaining account of their difficulties hiding out in an old shed, but very quickly the reader is aware that something is deeply wrong. It's not until quite late in the book that Pete grasps that his father is actually mentally ill, and that the danger he fears from helicopters and pursuers exists only in his mind.

This is a poignant little book. Luckily Pete connects with old friends and makes new ones, and his father finds the help he needs. It's not an unalloyed happy ending, but there is definitely hope on the horizon. Though this novel is only fifteen years old, I have a nasty suspicion that there might be less support out there for the Pete's dads of this world than there used to be. Helicopter Man would be a great resource for kids with mental illness in the family, and it's a good story in its own right. Set in Melbourne, which is a bonus.

Disclaimer: I purchased this book after having lunch with Elizabeth, who is a lovely person. Totally didn't influence my opinion, though!

Pete and his dad are on the run. Pete's diary offers us an entertaining account of their difficulties hiding out in an old shed, but very quickly the reader is aware that something is deeply wrong. It's not until quite late in the book that Pete grasps that his father is actually mentally ill, and that the danger he fears from helicopters and pursuers exists only in his mind.

This is a poignant little book. Luckily Pete connects with old friends and makes new ones, and his father finds the help he needs. It's not an unalloyed happy ending, but there is definitely hope on the horizon. Though this novel is only fifteen years old, I have a nasty suspicion that there might be less support out there for the Pete's dads of this world than there used to be. Helicopter Man would be a great resource for kids with mental illness in the family, and it's a good story in its own right. Set in Melbourne, which is a bonus.

Disclaimer: I purchased this book after having lunch with Elizabeth, who is a lovely person. Totally didn't influence my opinion, though!

17.12.19

The Wych Elm

The Wych Elm (which Blogger auto-correct insisted several times on changing to The Which Elm, and which seems to have been published in the US as The Witch Elm) is the first book I've read by Irish crime novelist Tana French. And it's very, very good.

Apparently this is French's first departure from a series about the fictional Dublin Murder Squad, and it centres on golden boy Toby whose life is upended after a brutal home invasion which leaves him mentally and physically wounded, and then by the discovery of a skeleton inside a tree at the house of his uncle Hugo, where he's staying to recover. With his newly unreliable memory, Toby has to wonder if he himself might have been the murderer... and if not him, then who?

Another character dying of a brain tumour! It's so weird that I seem to have been attracting these books all year; it's definitely not intentional. Hugo's cancer is ruthless but relatively slow moving; he hangs around long enough to take care of Toby even though Toby is supposed to be keeping an eye on him. This is a study of privilege, taken for granted and then lost; about being blithely oblivious to things that are obvious to others; about how it feels to be wrecked, and how fragile is our knowledge of ourselves.

This is a thick, densely layered but very readable novel, an intelligent, literary murder mystery. Is there a more satisfying kind of holiday book? And lucky me, now I know about Tana French, there are at least six more terrific books for me to explore!

Apparently this is French's first departure from a series about the fictional Dublin Murder Squad, and it centres on golden boy Toby whose life is upended after a brutal home invasion which leaves him mentally and physically wounded, and then by the discovery of a skeleton inside a tree at the house of his uncle Hugo, where he's staying to recover. With his newly unreliable memory, Toby has to wonder if he himself might have been the murderer... and if not him, then who?

Another character dying of a brain tumour! It's so weird that I seem to have been attracting these books all year; it's definitely not intentional. Hugo's cancer is ruthless but relatively slow moving; he hangs around long enough to take care of Toby even though Toby is supposed to be keeping an eye on him. This is a study of privilege, taken for granted and then lost; about being blithely oblivious to things that are obvious to others; about how it feels to be wrecked, and how fragile is our knowledge of ourselves.

This is a thick, densely layered but very readable novel, an intelligent, literary murder mystery. Is there a more satisfying kind of holiday book? And lucky me, now I know about Tana French, there are at least six more terrific books for me to explore!

Labels:

book response,

Irish literature,

mystery,

Tana French

15.12.19

Marlow Brown: Scientist in the Making

Disclaimer: I do know Kesta Fleming, author of Marlow Brown: Scientist in the Making, from the Convent Book Group, but she did not ask me to endorse this book (and I paid for it myself).

However, I have no qualms about endorsing this junior chapter book! It's a simple story about budding scientist Marlow, whose experiments with ants, dogs and Mum's white roses cause such chaos at home that she seems likely to be banned from experimenting altogether.

With a push to encourage girls into STEM subjects, this is an appealing and timely book, and I loved that it includes ideas for the reader's own experiments at the back. Loads of fun and educational too. Hopefully this will be the first of a long series.

However, I have no qualms about endorsing this junior chapter book! It's a simple story about budding scientist Marlow, whose experiments with ants, dogs and Mum's white roses cause such chaos at home that she seems likely to be banned from experimenting altogether.

With a push to encourage girls into STEM subjects, this is an appealing and timely book, and I loved that it includes ideas for the reader's own experiments at the back. Loads of fun and educational too. Hopefully this will be the first of a long series.

13.12.19

Tennis Shoes

There is supposed to be a bit of a curse on books with green covers. Certainly I would say that Human Croquet, which I read recently, was not one of Kate Atkinson's best. And the same can be said for Tennis Shoes, which was that rare beast, a Noel Streatfeild title I hadn't read before.

I don't think I ever came across this book as a child. Even if I had, I wouldn't have picked it up as I had zero interest in tennis. Unfortunately this seems to have also been the case for Streatfeild herself, who was apparently looking for a follow-up to the hugely successful Ballet Shoes and decided (or perhaps the publisher decided) that tennis would fit the bill. After spending months dutifully researching for this book of a family of tennis stars, Streatfeild reportedly said, 'I know one thing for sure, I simply hate tennis.' (According to the note at the back of this edition, she later changed her mind and Tennis Shoes 'became one of her favourite books.' Yeah, right.)

Again we have the weird Nanny-figure/governess in Pinny (and the children's mother, a doctor's wife, seems to do nothing all day). Again we have conscientious older children, twins Jim and Susan, who work hard at their tennis but lack what we would now call X factor. Youngest brother David loves his dog, Agag, and long words. And we have 'difficult' middle child Nicky (did you know that Noel Streatfeild was a middle child??) who unexpectedly becomes the real star of the family.

This is a competent, amusing tale from Streatfeild, but her lack of connection to sport is clear. Part of the enduring charm of her books is the intimate detail and the acute understanding of how it feels to be part of a theatre production or to struggle with ballet steps. Tennis Shoes goes through the motions but I never felt I got inside the tennis experience. I think the only other 'sporty' book Streatfeild wrote was White Boots, about ice skating, which is much closer to dance than tennis will ever be!

I don't think I ever came across this book as a child. Even if I had, I wouldn't have picked it up as I had zero interest in tennis. Unfortunately this seems to have also been the case for Streatfeild herself, who was apparently looking for a follow-up to the hugely successful Ballet Shoes and decided (or perhaps the publisher decided) that tennis would fit the bill. After spending months dutifully researching for this book of a family of tennis stars, Streatfeild reportedly said, 'I know one thing for sure, I simply hate tennis.' (According to the note at the back of this edition, she later changed her mind and Tennis Shoes 'became one of her favourite books.' Yeah, right.)

Again we have the weird Nanny-figure/governess in Pinny (and the children's mother, a doctor's wife, seems to do nothing all day). Again we have conscientious older children, twins Jim and Susan, who work hard at their tennis but lack what we would now call X factor. Youngest brother David loves his dog, Agag, and long words. And we have 'difficult' middle child Nicky (did you know that Noel Streatfeild was a middle child??) who unexpectedly becomes the real star of the family.

This is a competent, amusing tale from Streatfeild, but her lack of connection to sport is clear. Part of the enduring charm of her books is the intimate detail and the acute understanding of how it feels to be part of a theatre production or to struggle with ballet steps. Tennis Shoes goes through the motions but I never felt I got inside the tennis experience. I think the only other 'sporty' book Streatfeild wrote was White Boots, about ice skating, which is much closer to dance than tennis will ever be!

11.12.19

Tea by the Nursery Fire

I found this short, large print biography in the local library while I was on a quest for Noel Streatfeild books. For a Streatfeild fan, Tea by the Nursery Fire: A Children's Nanny at the Turn of the Century is fascinating reading. It's the biography of Emily Huckwell, familiar to readers of A Vicarage Family as Grand-Nanny, the beloved nanny of Victoria's father (Victoria being the thinly disguised figure of Streatfeild herself).

Emily was born in Sussex in the 1870s and at twelve years old, went into domestic service. She started as nursery maid and ended up as head nanny. At one point she did contemplate marriage, but her fiancé was killed in an accident and for the rest of her life, she devoted herself to 'her' children. Certainly Streatfeild's father was devoted to her, much more so than to his actual mother. No wonder, because Emily brought him up, loved and disciplined him, and he rewarded her with his first love.

This book is a window into another time, where people 'knew their place' and didn't question it. Emily is clearly the origin of all those comfortable, loving but strict non-mother figures that litter Streatfeild's fiction -- Nana in Ballet Shoes, Peaseblossom in The Painted Garden, Pinny in Tennis Shoes. Long after nannies had disappeared from the average middle class household (let alone the genteel poor who form the majority of Streatfeild's fictional families), these figures keep cropping up, with increasingly strange relationships to justify their presence -- an old school friend, daughter of a former patient -- and these women, always single, seem content to join the household as something between a servant and a relative, always doing the worst chores, the mending, escorting the children round town, and never complaining about their lot. They are always a fount of folk wisdom, which it transpires comes straight from the lips of Emily Huckwell: Satan finds work for idle hands, don't care was made to care, it will all be Sir Garnet.

It seems that Grand-Nanny was such an integral part of Streatfeild's own family that she found it impossible to imagine any family without a similar figure as part of it, taking up the slack from Streatfeild's universally useless mother-characters.

Emily was born in Sussex in the 1870s and at twelve years old, went into domestic service. She started as nursery maid and ended up as head nanny. At one point she did contemplate marriage, but her fiancé was killed in an accident and for the rest of her life, she devoted herself to 'her' children. Certainly Streatfeild's father was devoted to her, much more so than to his actual mother. No wonder, because Emily brought him up, loved and disciplined him, and he rewarded her with his first love.

This book is a window into another time, where people 'knew their place' and didn't question it. Emily is clearly the origin of all those comfortable, loving but strict non-mother figures that litter Streatfeild's fiction -- Nana in Ballet Shoes, Peaseblossom in The Painted Garden, Pinny in Tennis Shoes. Long after nannies had disappeared from the average middle class household (let alone the genteel poor who form the majority of Streatfeild's fictional families), these figures keep cropping up, with increasingly strange relationships to justify their presence -- an old school friend, daughter of a former patient -- and these women, always single, seem content to join the household as something between a servant and a relative, always doing the worst chores, the mending, escorting the children round town, and never complaining about their lot. They are always a fount of folk wisdom, which it transpires comes straight from the lips of Emily Huckwell: Satan finds work for idle hands, don't care was made to care, it will all be Sir Garnet.

It seems that Grand-Nanny was such an integral part of Streatfeild's own family that she found it impossible to imagine any family without a similar figure as part of it, taking up the slack from Streatfeild's universally useless mother-characters.

Labels:

biography,

book response,

Noel Streatfeild

9.12.19

The Final Solution

I found this very slim 2004 novella in a secondhand book shop (not Brown & Bunting, a different one at the top of High St whose name escapes me). It's barely 130 pages, including illustrations, but it's charming.

I've found Michael Chabon a little patchy in the past. Loved Kavalier and Clay; Gentlemen of the Road, meh. I was impressed to see that he was one of the creators of Netflix's terrific show Unbelievable. So I'll always give him the benefit of the doubt. The Final Solution is, of course, the last case of Sherlock Holmes, though the old gentleman is never named. We are in wartime Sussex, where Holmes has retired with his hives, when a murder and a mysterious disappearance require his involvement.

The plot itself is not amazingly satisfying, but the writing is gorgeous and the atmosphere of regret and nostalgia is tenderly conveyed. A quick read, but a sweet one.

I've found Michael Chabon a little patchy in the past. Loved Kavalier and Clay; Gentlemen of the Road, meh. I was impressed to see that he was one of the creators of Netflix's terrific show Unbelievable. So I'll always give him the benefit of the doubt. The Final Solution is, of course, the last case of Sherlock Holmes, though the old gentleman is never named. We are in wartime Sussex, where Holmes has retired with his hives, when a murder and a mysterious disappearance require his involvement.

The plot itself is not amazingly satisfying, but the writing is gorgeous and the atmosphere of regret and nostalgia is tenderly conveyed. A quick read, but a sweet one.

7.12.19

The Painted Garden

Re-reading The Secret Garden made me want to revisit this Noel Streatfeild book from 1949, in which an English family visit California and the 'difficult' middle child, Jane, finds herself cast as Mary in a film of The Secret Garden. There actually was a film version made by MGM in 1949 and it seems that Streatfeild did some research on set, though there is a note at the start of the book disclaiming any similarities.

Jane's family contains the usual array of Streatfeild characters. Rachel is the conscientious eldest daughter, a ballet dancer. Tim is the precocious youngest son, a gifted pianist. There is the usual non-parent helper attached to the family, in this case a school friend of the children's mother known bizarrely as Peaseblossom. Stroppy Jane is not talented at anything and wants to be a dog trainer, so she is charmed by the boy who plays Dickon.

The aspect of this book that always stayed with me was the clash between sunny America and post-war Britain. The children don't stay up for dinner with the adults but eat early supper of cereal and fruit on trays then go to bed at six thirty. The girls' clothes are humiliatingly shabby (Streatfeild is always aware of clothes). Transport is a problem as the children's aunt Cora, with whom they are staying, won't drive them all over town and public transport is non-existent, which is probably still true.

The best part is the reappearance of Posy and Pauline Fossil from Ballet Shoes. Pauline is now a film star and Posy is her same irrepressible self, dancing in movies but still part of the great Manoff's company. Posy befriends Rachel and Peaseblossom gets on well with Nana -- no wonder, because they are essentially the same character in different bodies.

In some ways Noel Streatfeild does write the same story over and over, but I enjoy the template so much that there is always something to relish in each variation. Comfort reading of the highest order!

Jane's family contains the usual array of Streatfeild characters. Rachel is the conscientious eldest daughter, a ballet dancer. Tim is the precocious youngest son, a gifted pianist. There is the usual non-parent helper attached to the family, in this case a school friend of the children's mother known bizarrely as Peaseblossom. Stroppy Jane is not talented at anything and wants to be a dog trainer, so she is charmed by the boy who plays Dickon.

The aspect of this book that always stayed with me was the clash between sunny America and post-war Britain. The children don't stay up for dinner with the adults but eat early supper of cereal and fruit on trays then go to bed at six thirty. The girls' clothes are humiliatingly shabby (Streatfeild is always aware of clothes). Transport is a problem as the children's aunt Cora, with whom they are staying, won't drive them all over town and public transport is non-existent, which is probably still true.

The best part is the reappearance of Posy and Pauline Fossil from Ballet Shoes. Pauline is now a film star and Posy is her same irrepressible self, dancing in movies but still part of the great Manoff's company. Posy befriends Rachel and Peaseblossom gets on well with Nana -- no wonder, because they are essentially the same character in different bodies.

In some ways Noel Streatfeild does write the same story over and over, but I enjoy the template so much that there is always something to relish in each variation. Comfort reading of the highest order!

5.12.19

Human Croquet

This was a very peculiar book. I'm quite glad I started reading Kate Atkinson with the Jackson Brodie books because if I'd read Human Croquet (her second novel) or even Behind the Scenes at the Museum (her debut) first, I'm not sure I would have persisted.

Human Croquet starts out with a similar feel to Behind the Scenes -- a crowded, inter-generational family saga with lots of characters, very eventful, busy with word-play and inner dialogue, swooping back and forth in time and place. After the sparse elegance of Between a Wolf and a Dog, it felt as if there was almost too much going on.

But then just when I felt as if I had a handle on it, Human Croquet swerved in a different, disquieting direction that made me sit up. This was when the book became really good. Then there was another swerve and things just got really weird and stayed that way. I was not satisfied by the ultimate conclusion, though the section that dealt with Isobel's mother's story was absolutely masterful.

Also: false advertising! The blurb on the back made this novel sound like a time slip story with travel not just to Shakespeare's time, but involving actual William himself. Don't be fooled. The Shakespearean part is very short and doesn't come until very close to the end. Overall, I was slightly nonplussed by this novel. I'm not sorry I read it, but I couldn't help feeling that it could have done with a good edit and a bit of attention to structure.

Human Croquet starts out with a similar feel to Behind the Scenes -- a crowded, inter-generational family saga with lots of characters, very eventful, busy with word-play and inner dialogue, swooping back and forth in time and place. After the sparse elegance of Between a Wolf and a Dog, it felt as if there was almost too much going on.

But then just when I felt as if I had a handle on it, Human Croquet swerved in a different, disquieting direction that made me sit up. This was when the book became really good. Then there was another swerve and things just got really weird and stayed that way. I was not satisfied by the ultimate conclusion, though the section that dealt with Isobel's mother's story was absolutely masterful.

Also: false advertising! The blurb on the back made this novel sound like a time slip story with travel not just to Shakespeare's time, but involving actual William himself. Don't be fooled. The Shakespearean part is very short and doesn't come until very close to the end. Overall, I was slightly nonplussed by this novel. I'm not sorry I read it, but I couldn't help feeling that it could have done with a good edit and a bit of attention to structure.

3.12.19

Fair Play

This was SUCH an interesting book! I borrowed it from the library after someone mentioned it on Twitter -- it's about the division of domestic labour, essentially, and a technique for splitting it with your partner that will (hopefully) lead to efficiency, more time, less resentment and shared responsibility for the physical and mental load of running a household.

Eve Rodsky sets up Fair Play as a game. She divides household and family work into 100 tasks in four suits: Home (meals, laundry, cleaning etc), Out (school liaison, cars, bills, travel etc), Caregiving (pets, bedtime routine, homework, medical appointments etc) and Magic (gestures of love, fun, holidays, magical beings). Some of these tasks are further designated as Daily Grind, things that have to be done, usually at a certain time, or the place falls apart (like meals, laundry, transport, grocery shopping).

The holder of any particular card, say Laundry, takes full responsibility for Conception, Planning and Execution of that card -- so not just, can you put a load of washing on, love? But noticing that the basket is full, sorting the wash, loading the machine, hanging it out, bringing it in, sorting and folding and putting away, noticing that we're almost out of detergent and adding it to the shopping list, making sure that X's school shirt gets washed by Monday and Y's socks get soaked before soccer day.

Of course the first thing I did was sit down and work out who holds which cards in our house. We only play 60 cards out of Rodsky's hundred, and I added in an extra one (transport of my parents). Eleven of those are shared (a big no-no in Rodsky's system), I hold 29 and M holds 21. Apparently, lucky me, couples report feeling equity when the husband holds... wait for it... 21 cards!! And I do feel that our split is fairly equitable.

But one thing that did leap out at me is that I hold the vast majority of Daily Grinds. So, the not negotiable, non-deferrable, daily tedium like cooking and washing and getting kids off to school falls largely to me. On the other hand, M has more control over when he chooses to play his cards, like Lawn & Plants, Home Maintenance, Cash & Bills. This helped me to clarify why I still sometimes feel hard-done-by even when we've both spent a weekend working hard -- I have less choice and control about what I do and when. People gotta get fed...

Anyway, there's a lot more to it and I doubt that I'll actually change up anything much, but it was certainly food for thought and conversation. Well worth reading.

Eve Rodsky sets up Fair Play as a game. She divides household and family work into 100 tasks in four suits: Home (meals, laundry, cleaning etc), Out (school liaison, cars, bills, travel etc), Caregiving (pets, bedtime routine, homework, medical appointments etc) and Magic (gestures of love, fun, holidays, magical beings). Some of these tasks are further designated as Daily Grind, things that have to be done, usually at a certain time, or the place falls apart (like meals, laundry, transport, grocery shopping).

The holder of any particular card, say Laundry, takes full responsibility for Conception, Planning and Execution of that card -- so not just, can you put a load of washing on, love? But noticing that the basket is full, sorting the wash, loading the machine, hanging it out, bringing it in, sorting and folding and putting away, noticing that we're almost out of detergent and adding it to the shopping list, making sure that X's school shirt gets washed by Monday and Y's socks get soaked before soccer day.

Of course the first thing I did was sit down and work out who holds which cards in our house. We only play 60 cards out of Rodsky's hundred, and I added in an extra one (transport of my parents). Eleven of those are shared (a big no-no in Rodsky's system), I hold 29 and M holds 21. Apparently, lucky me, couples report feeling equity when the husband holds... wait for it... 21 cards!! And I do feel that our split is fairly equitable.

But one thing that did leap out at me is that I hold the vast majority of Daily Grinds. So, the not negotiable, non-deferrable, daily tedium like cooking and washing and getting kids off to school falls largely to me. On the other hand, M has more control over when he chooses to play his cards, like Lawn & Plants, Home Maintenance, Cash & Bills. This helped me to clarify why I still sometimes feel hard-done-by even when we've both spent a weekend working hard -- I have less choice and control about what I do and when. People gotta get fed...

Anyway, there's a lot more to it and I doubt that I'll actually change up anything much, but it was certainly food for thought and conversation. Well worth reading.

Labels:

book response,

gender,

housework,

non-fiction

30.11.19

Between A Wolf And A Dog

What a beautiful novel. Also borrowed from my friend Christine, this is the first time I've read Georgia Blain's writing. I was aware of the tragic irony of her story, that she'd just finished writing a novel about a woman dying of a brain tumour when she was diagnosed herself with the same kind of aggressive, incurable tumour (incidentally, the same glioblastoma that killed my friend Sandra). Knowing this, I was wary of approaching Between A Wolf and A Dog, but I needn't have worried.

I wasn't familiar with the expression 'between a wolf and a dog' (it's French) but it refers to the hour of twilight when apparently it's difficult to distinguish between those two animals. The whole novel is like this: strong but delicately poised, at once tender and steely. It takes place over a single rainy Sydney day, following Hilary as she contemplates her illness and the decision she's taken; her daughters April, a singer, and Ester, a therapist, estranged over the infidelity of April and Ester's pollster husband Lawrence. The narrative dips back to happier and also more fraught times, and Ester's patients introduce vignettes of lost love, loneliness and pain.

This was the kind of novel I aspired to achieve when I first began writing -- acute psychological insight married to beautiful, sparse, lyrical prose. I never quite got there, and discovered my strengths lay elsewhere (to put it kindly). What a terrible loss is Georgia Blain, but how fortunate we are that she was with us long enough to produce superb work like this.

I wasn't familiar with the expression 'between a wolf and a dog' (it's French) but it refers to the hour of twilight when apparently it's difficult to distinguish between those two animals. The whole novel is like this: strong but delicately poised, at once tender and steely. It takes place over a single rainy Sydney day, following Hilary as she contemplates her illness and the decision she's taken; her daughters April, a singer, and Ester, a therapist, estranged over the infidelity of April and Ester's pollster husband Lawrence. The narrative dips back to happier and also more fraught times, and Ester's patients introduce vignettes of lost love, loneliness and pain.

This was the kind of novel I aspired to achieve when I first began writing -- acute psychological insight married to beautiful, sparse, lyrical prose. I never quite got there, and discovered my strengths lay elsewhere (to put it kindly). What a terrible loss is Georgia Blain, but how fortunate we are that she was with us long enough to produce superb work like this.

27.11.19

The Woman Who Cracked the Anxiety Code

The Woman Who Cracked the Anxiety Code was Dr Claire Weekes, an Australian doctor who wrote self-help books about anxiety and panic attacks which sold millions of copies all over the world, and still sell well today. Yet I had never heard of her!

Judith Hoare's biography is sub-titled The Extraordinary Life of Dr Claire Weekes and in many ways Weekes' life was indeed extraordinary. She was a scientific researcher in the 1920s, when women were barely admitted to university, and her pioneering work on lizard reproduction is still cited today. She reinvented herself several times, planning a musical career, then an upmarket travel agency. The latter plan being kiboshed by the outbreak of WWII, she went back to university and qualified as a GP. Then, in the 1960s and beyond, came the self-help books.

This is where her story, sadly, becomes less extraordinary. Being a woman, and a mere general practitioner rather than a psychiatrist, writing for a popular audience (so she could actually help as many people as possible) rather than in academic journals or psychiatric forums, her work was belittled and overlooked. And yet her mantra (based on both scientific knowledge and personal experience) -- Face, Accept, Float, Let Time Pass -- presaged modern approaches to dealing with anxiety like CBT and ACT. Her key insight was not to fight the feelings of panic, but to let them wash through you, and to "float" through them.

I would have liked a little more on her work, which was sometimes presented in a slightly confusing way by Hoare, but overall this was a fascinating introduction to a woman who should be more widely known. Borrowed from my friend Christine.

Judith Hoare's biography is sub-titled The Extraordinary Life of Dr Claire Weekes and in many ways Weekes' life was indeed extraordinary. She was a scientific researcher in the 1920s, when women were barely admitted to university, and her pioneering work on lizard reproduction is still cited today. She reinvented herself several times, planning a musical career, then an upmarket travel agency. The latter plan being kiboshed by the outbreak of WWII, she went back to university and qualified as a GP. Then, in the 1960s and beyond, came the self-help books.

This is where her story, sadly, becomes less extraordinary. Being a woman, and a mere general practitioner rather than a psychiatrist, writing for a popular audience (so she could actually help as many people as possible) rather than in academic journals or psychiatric forums, her work was belittled and overlooked. And yet her mantra (based on both scientific knowledge and personal experience) -- Face, Accept, Float, Let Time Pass -- presaged modern approaches to dealing with anxiety like CBT and ACT. Her key insight was not to fight the feelings of panic, but to let them wash through you, and to "float" through them.

I would have liked a little more on her work, which was sometimes presented in a slightly confusing way by Hoare, but overall this was a fascinating introduction to a woman who should be more widely known. Borrowed from my friend Christine.

Labels:

Australian women writers,

biography,

book response,

psychology

23.11.19

When the Lyrebird Calls

I'm not sure if this is the first time I've found myself reading three books at the same time, all by Australian women writers.

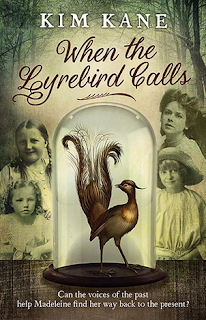

I've been meaning to read Kim Kane's time slip novel, When the Lyrebird Calls, since it first came out, and I found this copy at Brown & Bunting. My ladies' book group thought highly of it, but someone said, what a shame the cover is so drab.

Having read the book, I think the designer (ooh, I just discovered it's Debra Billson, who has produced a gorgeous design for my forthcoming middle-grade book, The January Stars) has done an amazing job of tracking down contemporary photographs that resemble the four girls in the story. And, spookily, yesterday I happened to look up that first classic Australian time-slip novel, Ruth Park's Playing Beatie Bow, and noticed the original Puffin edition cover:

As Kim Kane makes a point of referencing Beatie Bow in her acknowledgements, the similarity in these covers can't be a coincidence. But I'm not sure how many readers, especially young readers, would pick up on the homage, particularly as it eluded a bunch of highly experienced school librarians and children's literature enthusiasts (shame on us).

Aanyway, I wasn't sure I was going to enjoy this book when it opened with a scene of three young girls destroying a fancy doll. I have a tendency to feel sorry for inanimate objects and this overt cruelty didn't endear the young protagonists to me. But once the time slip happened, I was all in. Madeleine doesn't travel back and forth but stays in 1900 for an extended period, which gives a good solid look at the issues of the time (Federation, suffrage, racism, spiritualism) as well as the tangled family dynamics of the Williamson household where Madeleine ends up. (Extra points to Gertie for attending my alma mater, PLC!) It's not till the final chapter, back in her own time, that Madeleine discovers some family secrets that make sense of what she's seen.

Kim Kane has a quirky and often humorous turn of phrase that adds to the enjoyment, and I appreciated the feminist emphasis as well as the sensitive portrayal of a young Aboriginal man (he deserves his own book, I reckon). Loved it!

I've been meaning to read Kim Kane's time slip novel, When the Lyrebird Calls, since it first came out, and I found this copy at Brown & Bunting. My ladies' book group thought highly of it, but someone said, what a shame the cover is so drab.

Having read the book, I think the designer (ooh, I just discovered it's Debra Billson, who has produced a gorgeous design for my forthcoming middle-grade book, The January Stars) has done an amazing job of tracking down contemporary photographs that resemble the four girls in the story. And, spookily, yesterday I happened to look up that first classic Australian time-slip novel, Ruth Park's Playing Beatie Bow, and noticed the original Puffin edition cover:

As Kim Kane makes a point of referencing Beatie Bow in her acknowledgements, the similarity in these covers can't be a coincidence. But I'm not sure how many readers, especially young readers, would pick up on the homage, particularly as it eluded a bunch of highly experienced school librarians and children's literature enthusiasts (shame on us).

Aanyway, I wasn't sure I was going to enjoy this book when it opened with a scene of three young girls destroying a fancy doll. I have a tendency to feel sorry for inanimate objects and this overt cruelty didn't endear the young protagonists to me. But once the time slip happened, I was all in. Madeleine doesn't travel back and forth but stays in 1900 for an extended period, which gives a good solid look at the issues of the time (Federation, suffrage, racism, spiritualism) as well as the tangled family dynamics of the Williamson household where Madeleine ends up. (Extra points to Gertie for attending my alma mater, PLC!) It's not till the final chapter, back in her own time, that Madeleine discovers some family secrets that make sense of what she's seen.

Kim Kane has a quirky and often humorous turn of phrase that adds to the enjoyment, and I appreciated the feminist emphasis as well as the sensitive portrayal of a young Aboriginal man (he deserves his own book, I reckon). Loved it!

20.11.19

Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine

I picked up my copy of Gail Honeyman's smash hit, Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine, from Royal Talbot Rehabilitation Hospital's second hand book shelves earlier this year. My copy is plastered with even more award stickers than the one in the picture, and after reading it, it's easy to see how it's amassed so many accolades.

This is a mystery story, in some ways a horror story, but packaged up in highly entertaining wrapping. Eleanor Oliphant tells her own story, and her voice is fresh, funny and very distinctive, even while she's recounting a story of pain, loneliness and childhood abuse that might be impossible to digest otherwise. At times the reader almost feels guilty for finding Eleanor amusing, as she is clearly dealing with a legacy of tremendous suffering.

As always, salvation lies in connection. Through small acts of kindness, Eleanor re-enters the world she has shut out, and it's rewarding to journey with her, as bit by bit, she blossoms. She is supposed to be about thirty, but sometimes she reads like a woman twice that age. A bonus is that the book is set in Glasgow and lovely Scottishness lies over the whole book like a mist. An excellent pick-up.

This is a mystery story, in some ways a horror story, but packaged up in highly entertaining wrapping. Eleanor Oliphant tells her own story, and her voice is fresh, funny and very distinctive, even while she's recounting a story of pain, loneliness and childhood abuse that might be impossible to digest otherwise. At times the reader almost feels guilty for finding Eleanor amusing, as she is clearly dealing with a legacy of tremendous suffering.

As always, salvation lies in connection. Through small acts of kindness, Eleanor re-enters the world she has shut out, and it's rewarding to journey with her, as bit by bit, she blossoms. She is supposed to be about thirty, but sometimes she reads like a woman twice that age. A bonus is that the book is set in Glasgow and lovely Scottishness lies over the whole book like a mist. An excellent pick-up.

16.11.19

Through the Language Glass

The younger daughter begged me to order Guy Deutscher's Through the Language Glass for her, prompted by Stephen Fry's fulsome endorsement (see above: 'jaw-droppingly wonderful' and 'left me breathless and dizzy with delight').

Well, suffice to say that both the daughter and I felt that Stephen Fry had gone a little overboard with his praise this time. She slogged through it first, heroically sticking to her routine of one chapter per night (the chapters are quite long), then handed it to me. That was months ago, but I've finally managed to push through to the end.

This is not a terrible book, by any means. The subject matter is fascinating (how does the language we speak influence our perception of the world?) and Deutscher does his best to jolly us along with linguistic humour. But it's a thorough (some may say, too thorough) survey of a quite dry academic field, and its conclusions are fairly underwhelming, to wit, yes, language does influence some aspects of how we perceive the world, but not much, and only in certain areas (colour, gender, spatial orientation).

Probably the most interesting section dealt with one Australian Aboriginal language (Guugu Yimithirr) which requires its speakers to take note of the compass directions whenever they describe the position of something. So instead of saying, 'there is an ant to the right of my foot,' they would say, 'there is an ant to the south-west of my foot.' This means they are constantly, unconsciously orienting themselves geographically in their surroundings. That would be a handy skill to have.

Well, suffice to say that both the daughter and I felt that Stephen Fry had gone a little overboard with his praise this time. She slogged through it first, heroically sticking to her routine of one chapter per night (the chapters are quite long), then handed it to me. That was months ago, but I've finally managed to push through to the end.

This is not a terrible book, by any means. The subject matter is fascinating (how does the language we speak influence our perception of the world?) and Deutscher does his best to jolly us along with linguistic humour. But it's a thorough (some may say, too thorough) survey of a quite dry academic field, and its conclusions are fairly underwhelming, to wit, yes, language does influence some aspects of how we perceive the world, but not much, and only in certain areas (colour, gender, spatial orientation).

Probably the most interesting section dealt with one Australian Aboriginal language (Guugu Yimithirr) which requires its speakers to take note of the compass directions whenever they describe the position of something. So instead of saying, 'there is an ant to the right of my foot,' they would say, 'there is an ant to the south-west of my foot.' This means they are constantly, unconsciously orienting themselves geographically in their surroundings. That would be a handy skill to have.

13.11.19

Sick Bay

Holding Nova Weetman's latest junior fiction novel, Sick Bay, in my hands was a bittersweet experience. The cover of Sick Bay was the last published artwork by my dear friend Sandra Eterovic before she died, almost exactly a year ago, of brain cancer. (And yes, the awful irony of the title is not lost on me.) There is a lovely tribute to Sandra from Nova Weetman in the acknowledgments; Sandra had also supplied the cover artwork for Weetman's previous two books.

Sick Bay is a story of friendship. Riley has diabetes, but dealing with her anxiously controlling mother is a bigger problem than her health. Meg takes refuge in Sick Bay when life becomes too hard -- her father has died and her mother has sunk into a deep depression. Compounding the girls' personal problems is the landscape of friendship at school with one girl, Lina, who dispenses and withholds her approval like a weapon.

Come to think of it, Sick Bay is really about control -- the things you can control and the things you can't. Riley is struggling to take control of her own diabetes management, while Meg is powerless to help her mother. These are Grade 6 pupils, with high school on the horizon, and the world is about to get bigger and even harder to navigate. Nova Weetman writes so beautifully about friendship and family and the blindsides of mental health. Perhaps it's appropriate that this was the last cover from Sandra before we lost her.

Sick Bay is a story of friendship. Riley has diabetes, but dealing with her anxiously controlling mother is a bigger problem than her health. Meg takes refuge in Sick Bay when life becomes too hard -- her father has died and her mother has sunk into a deep depression. Compounding the girls' personal problems is the landscape of friendship at school with one girl, Lina, who dispenses and withholds her approval like a weapon.

Come to think of it, Sick Bay is really about control -- the things you can control and the things you can't. Riley is struggling to take control of her own diabetes management, while Meg is powerless to help her mother. These are Grade 6 pupils, with high school on the horizon, and the world is about to get bigger and even harder to navigate. Nova Weetman writes so beautifully about friendship and family and the blindsides of mental health. Perhaps it's appropriate that this was the last cover from Sandra before we lost her.

6.11.19

On Writing

I should confess at the outset that I haven't read much -- or any, really -- of Stephen King's works, though of course I recognise what a hugely successful author he is. His subject matter, often shading into horror, is not my cup of tea.

But he certainly knows what he's talking about when it comes to the subject of writing itself, and this slim volume On Writing has terrific, pithy and straightforward advice about the craft, as well as including an interesting autobiographical section and an equally interesting account of the road accident that nearly killed him while he was writing it.

He has paid his dues, beginning his writing career while holding down a hideous job in a commercial laundry and living with his young family in a trailer, tapping out his first books on his knees. So he's earned his success and I don't begrudge it to him.

But Stephen. Come on. He describes his current working day: mornings, writing with the door shut to prevent interruptions until you reach your daily target (for him, 2,000 words; lesser mortals might aim for 1,000). Afternoons: naps and letters. Evenings: hanging out with the family, walking, reading. That sounds, frankly, idyllic.

When do you do the housework, Stephen? When do you make the lunches and dinner for everyone and do the grocery shopping? When do you drive your mum to the doctor and your anxious teenager to school? When do you clean out the rabbit and vacuum the floors? When do you hang on the phone to Centrelink to sort out the finances of your disabled sibling? How do you shoehorn all that in, Stephen? Or is there someone in the background taking care of all that?

To be fair, he is generous with his acknowledgement of his wife Tabby's help and encouragement along the way, and I have no doubt that he works hard at his job. But wow, wouldn't it be nice to be able to shut that door in the morning and never be interrupted.

But he certainly knows what he's talking about when it comes to the subject of writing itself, and this slim volume On Writing has terrific, pithy and straightforward advice about the craft, as well as including an interesting autobiographical section and an equally interesting account of the road accident that nearly killed him while he was writing it.

He has paid his dues, beginning his writing career while holding down a hideous job in a commercial laundry and living with his young family in a trailer, tapping out his first books on his knees. So he's earned his success and I don't begrudge it to him.

But Stephen. Come on. He describes his current working day: mornings, writing with the door shut to prevent interruptions until you reach your daily target (for him, 2,000 words; lesser mortals might aim for 1,000). Afternoons: naps and letters. Evenings: hanging out with the family, walking, reading. That sounds, frankly, idyllic.

When do you do the housework, Stephen? When do you make the lunches and dinner for everyone and do the grocery shopping? When do you drive your mum to the doctor and your anxious teenager to school? When do you clean out the rabbit and vacuum the floors? When do you hang on the phone to Centrelink to sort out the finances of your disabled sibling? How do you shoehorn all that in, Stephen? Or is there someone in the background taking care of all that?

To be fair, he is generous with his acknowledgement of his wife Tabby's help and encouragement along the way, and I have no doubt that he works hard at his job. But wow, wouldn't it be nice to be able to shut that door in the morning and never be interrupted.

Labels:

book response,

non-fiction,

writing,

writing habits

4.11.19

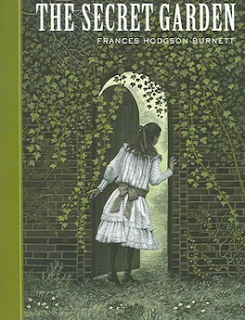

The Secret Garden

I first read my mother's copy of The Secret Garden from 1949, which I still own, very battered round the edges now. It was her favourite childhood book, and it's probably my all-time favourite, too (in a very crowded field).

The Secret Garden, published by Frances Hodgson Burnett in 1911, was somewhat overlooked in her lifetime, and wasn't even mentioned in her obituary. The sweet Cinderella story of A Little Princess and the ghastly Little Lord Fauntleroy were praised, but no one thought much of The Secret Garden. These days it's regarded as a classic, a masterpiece.

I love so much about this book. The notion of a secret, hidden, neglected garden, closed in by high walls and a locked door, is deliciously enticing. I love sour, lonely Mary Lennox; sturdy Dickon who communes with the wild animals; and fretful, sickly Colin. The scene where Mary and Colin scream at each other in a furious fight in the middle of the night used to give me such a thrill. And all the while, spring is creeping over the moor and reaching into the children's garden, healing their bodies and their minds.

It's been a few years since I last read The Secret Garden, and this time it was the mental health angle that jumped out at me. Neglected, unloved Mary is isolated and angry with the world; poor 'spoiled' Colin is actually tormented with anxiety; and his father, Mr Craven, is sunk in a deep depression after his wife's death. It's communion with nature, fresh air and sunshine and exercise, and a meaningful project in bringing the garden back to life, as well as connecting with each other, that brings them all back to health and happiness. It's a very simple story, but it's the very simplicity of the message that carries such power.

The Secret Garden, published by Frances Hodgson Burnett in 1911, was somewhat overlooked in her lifetime, and wasn't even mentioned in her obituary. The sweet Cinderella story of A Little Princess and the ghastly Little Lord Fauntleroy were praised, but no one thought much of The Secret Garden. These days it's regarded as a classic, a masterpiece.

I love so much about this book. The notion of a secret, hidden, neglected garden, closed in by high walls and a locked door, is deliciously enticing. I love sour, lonely Mary Lennox; sturdy Dickon who communes with the wild animals; and fretful, sickly Colin. The scene where Mary and Colin scream at each other in a furious fight in the middle of the night used to give me such a thrill. And all the while, spring is creeping over the moor and reaching into the children's garden, healing their bodies and their minds.

It's been a few years since I last read The Secret Garden, and this time it was the mental health angle that jumped out at me. Neglected, unloved Mary is isolated and angry with the world; poor 'spoiled' Colin is actually tormented with anxiety; and his father, Mr Craven, is sunk in a deep depression after his wife's death. It's communion with nature, fresh air and sunshine and exercise, and a meaningful project in bringing the garden back to life, as well as connecting with each other, that brings them all back to health and happiness. It's a very simple story, but it's the very simplicity of the message that carries such power.

Labels:

antique fiction,

book response,

garden,

re-reading

30.10.19

On The Beach

My elder daughter has been going through a dystopian phase lately (hey, she's doing VCE, what can you expect?). She asked me to buy her Cormac McCarthy's The Road and Nevil Shute's On The Beach, neither of which I had read myself. She devoured both of them at record speed. I haven't dared to open The Road, but I thought I'd give On The Beach a whirl.

It really is a surreal book. Famously, the novel follows the last few months in the lives of a handful of characters stranded in Melbourne, at the bottom of the world, as nuclear fallout from a catastrophic international war drifts southward. At the beginning of September or the end of August, everyone will get radiation sickness, and everyone will die. It's literally the end of the world.

What struck me most was how calm everyone was about it. Life goes on pretty much as usual. Oh, there's some drunkenness, some fast car racing, but people still plant their gardens, fret over their baby's teething, do their jobs, pay for their purchases in shops. Frankly, I would have expected a LOT more lawlessness, with no consequences to come.

Also, the tone is one of emotional restraint. Some characters are in denial, in one breath acknowledging that everything is coming to an end in a matter of weeks, and at the same time 'believing' that their family in the war zone is carrying on life as usual. Paradoxically, this is much more effective and horrifying than melodrama would have been, even if it is quite implausible.

It's weird and old-fashioned and unbelievable, but this is one dystopian novel that will stay with me. And hey, it's set in Melbourne!

It really is a surreal book. Famously, the novel follows the last few months in the lives of a handful of characters stranded in Melbourne, at the bottom of the world, as nuclear fallout from a catastrophic international war drifts southward. At the beginning of September or the end of August, everyone will get radiation sickness, and everyone will die. It's literally the end of the world.

What struck me most was how calm everyone was about it. Life goes on pretty much as usual. Oh, there's some drunkenness, some fast car racing, but people still plant their gardens, fret over their baby's teething, do their jobs, pay for their purchases in shops. Frankly, I would have expected a LOT more lawlessness, with no consequences to come.

Also, the tone is one of emotional restraint. Some characters are in denial, in one breath acknowledging that everything is coming to an end in a matter of weeks, and at the same time 'believing' that their family in the war zone is carrying on life as usual. Paradoxically, this is much more effective and horrifying than melodrama would have been, even if it is quite implausible.

It's weird and old-fashioned and unbelievable, but this is one dystopian novel that will stay with me. And hey, it's set in Melbourne!

28.10.19

Second Fiddle

Mary Wesley's Second Fiddle was her ninth novel, and it is a strange, rather disturbing book. It's not overly long, and some of the subplots fizzle out, with characters who seem to have been introduced for no particular purpose.

The story centres on Laura Thornby, at 45 a resolutely independent woman who guards her privacy and her emotions fiercely. In search of a diversion, she picks up with 23 year old Claud, an aspiring writer, and adroitly finds him a place to live (in a loft, naturally) and gainful employment while he's writing (an antique stall at the local market, which she helpfully stocks with items from her mother's attic). As Claud matures, Laura finds herself becoming more emotionally involved than she intended.

The sting in the novel's tail comes when it's revealed that Laura is the offspring of an incestuous union between brother and sister (not really a spoiler, as this is hinted at very early in the novel). This is apparently why she keeps herself so determinedly single and childless. Her elderly parents are a rather creepy pair, not surprisingly, and this shadow over Laura's origin made the whole novel very dark for me, and not as much fun as Mary Wesley can sometimes be.

Incest is a theme in several of Wesley's books (though seldom as overtly as here) and it's possible that she had a wartime romance with two brothers; it seems to have been an idea that intrigued her, at the very least. I wouldn't class Second Fiddle among her finest work.

The story centres on Laura Thornby, at 45 a resolutely independent woman who guards her privacy and her emotions fiercely. In search of a diversion, she picks up with 23 year old Claud, an aspiring writer, and adroitly finds him a place to live (in a loft, naturally) and gainful employment while he's writing (an antique stall at the local market, which she helpfully stocks with items from her mother's attic). As Claud matures, Laura finds herself becoming more emotionally involved than she intended.

The sting in the novel's tail comes when it's revealed that Laura is the offspring of an incestuous union between brother and sister (not really a spoiler, as this is hinted at very early in the novel). This is apparently why she keeps herself so determinedly single and childless. Her elderly parents are a rather creepy pair, not surprisingly, and this shadow over Laura's origin made the whole novel very dark for me, and not as much fun as Mary Wesley can sometimes be.

Incest is a theme in several of Wesley's books (though seldom as overtly as here) and it's possible that she had a wartime romance with two brothers; it seems to have been an idea that intrigued her, at the very least. I wouldn't class Second Fiddle among her finest work.

24.10.19

Sand Talk

A few times in your life, you come across a book that opens your eyes and your mind to a new way of looking at the world. For me, Bruce Chatwin's The Songlines was one of those books (though I now understand how problematic that book is). More recently, Alan Garner's The Voice That Thunders and Bruce Pascoe's Dark Emu have had a similar earth-shaking effect. And now there is Tyson Yunkaporta's Sand Talk.

This is a book I've been looking for for a long time. Ever since I started my research on Crow Country, nearly ten years ago now, and began to perceive tantalising hints of the Aboriginal world view, diametrically different to the Western assumptions I'd inherited, I've been longing for a clear, comprehensive guide to what Yunkaporta calls 'Indigenous thinking.' Now at last I've found it.

It's not easy to summarise the Aboriginal viewpoint and experience of the world, and I'm not going to presume to try to do it here. But one fundamental difference is that the Indigenous worldview never considers any one factor in isolation, never separates out one element of the picture to examine it 'objectively.' In the Aboriginal world, everything is connected, including us: land, Law, story, spirit, weather, plants and animals, humans, all inextricably intertwined. This is wisdom that the Western world is only just dimly beginning to reclaim.

Time is not a straight-line arrow into the future; it's an endlessly repeating cycle as the universe breathes in and out. All trouble begins with the thought I am greater than you. Aboriginal societies devote a lot of effort to trying to wipe out that tendency, the root of inequality, greed and oppression. Yunkaporta has an easy, engaging style, sprinkled with plenty of humour and anecdote -- this is far from a dry, academic read, but it's packed with ideas and questions nonetheless.

I don't necessarily find all of Yunkaporta's ideas comfortable. The chapter on violence was very confronting, the section on male-female relations didn't chime with my Western feminist standpoint. But Sand Talk has given me plenty to ponder on. I first read this book on the Kindle, and now I'm going to read it again in hard copy.

So good I've bought it twice! For a tight-arse like me, that's recommendation indeed.

This is a book I've been looking for for a long time. Ever since I started my research on Crow Country, nearly ten years ago now, and began to perceive tantalising hints of the Aboriginal world view, diametrically different to the Western assumptions I'd inherited, I've been longing for a clear, comprehensive guide to what Yunkaporta calls 'Indigenous thinking.' Now at last I've found it.

It's not easy to summarise the Aboriginal viewpoint and experience of the world, and I'm not going to presume to try to do it here. But one fundamental difference is that the Indigenous worldview never considers any one factor in isolation, never separates out one element of the picture to examine it 'objectively.' In the Aboriginal world, everything is connected, including us: land, Law, story, spirit, weather, plants and animals, humans, all inextricably intertwined. This is wisdom that the Western world is only just dimly beginning to reclaim.

Time is not a straight-line arrow into the future; it's an endlessly repeating cycle as the universe breathes in and out. All trouble begins with the thought I am greater than you. Aboriginal societies devote a lot of effort to trying to wipe out that tendency, the root of inequality, greed and oppression. Yunkaporta has an easy, engaging style, sprinkled with plenty of humour and anecdote -- this is far from a dry, academic read, but it's packed with ideas and questions nonetheless.

I don't necessarily find all of Yunkaporta's ideas comfortable. The chapter on violence was very confronting, the section on male-female relations didn't chime with my Western feminist standpoint. But Sand Talk has given me plenty to ponder on. I first read this book on the Kindle, and now I'm going to read it again in hard copy.

So good I've bought it twice! For a tight-arse like me, that's recommendation indeed.

21.10.19

Mr Romanov's Garden in the Sky

Isn't this a beautiful cover?

I chose Robert Newton's 2017 novel Mr Romanov's Garden in the Sky for the Convent Book Group, to fit with our November theme of Gardens. But it turns out that the book doesn't actually have much to do with gardening at all.

This is a terrific novel. But while I was reading it, I was haunted by the feeling which all writers know, which I'll call Authorial Serendipity. This happens when Author A (in this case, me) has a book coming out soon, and reads a book by Author B (in this instance, Robert Newton), which shares some of the characteristics of Author A's book... It's disconcerting, it happens all the time, and there's nothing you can do about it except grit your teeth and assure Author B that you have NOT plaigarised their work... it's just coincidence.

So. Mr Romanov's Garden in the Sky is about two kids and an old man who go on a road trip together. My forthcoming book, The January Stars, is also about two kids and an old man going on a road trip together. Mr Romanov's Garden is set in Melbourne (and also the road to Surfer's Paradise). The January Stars is also set in Melbourne (and various places around Victoria).

But. Mr Romanov's Garden is a fair bit darker than The January Stars. Lexie's dad is dead, her mum is a junkie, Mr Romanov has dementia, and the novel opens with someone throwing his dog off the top of the housing commissions. At this point, I confess, I almost abandoned the book. I'm glad I pushed on, but it was a hard hurdle to pass. I promise that there are NO dead dogs in The January Stars.

Also, The January Stars has a bit of magic in it. So I guess maybe they're not so similar after all.

I chose Robert Newton's 2017 novel Mr Romanov's Garden in the Sky for the Convent Book Group, to fit with our November theme of Gardens. But it turns out that the book doesn't actually have much to do with gardening at all.

This is a terrific novel. But while I was reading it, I was haunted by the feeling which all writers know, which I'll call Authorial Serendipity. This happens when Author A (in this case, me) has a book coming out soon, and reads a book by Author B (in this instance, Robert Newton), which shares some of the characteristics of Author A's book... It's disconcerting, it happens all the time, and there's nothing you can do about it except grit your teeth and assure Author B that you have NOT plaigarised their work... it's just coincidence.

So. Mr Romanov's Garden in the Sky is about two kids and an old man who go on a road trip together. My forthcoming book, The January Stars, is also about two kids and an old man going on a road trip together. Mr Romanov's Garden is set in Melbourne (and also the road to Surfer's Paradise). The January Stars is also set in Melbourne (and various places around Victoria).

But. Mr Romanov's Garden is a fair bit darker than The January Stars. Lexie's dad is dead, her mum is a junkie, Mr Romanov has dementia, and the novel opens with someone throwing his dog off the top of the housing commissions. At this point, I confess, I almost abandoned the book. I'm glad I pushed on, but it was a hard hurdle to pass. I promise that there are NO dead dogs in The January Stars.

Also, The January Stars has a bit of magic in it. So I guess maybe they're not so similar after all.

16.10.19

The Winter of Our Disconnect

The subtitle (see above) says it all. About ten years ago, American-born, Perth-based academic Susan Maushart decided to give her family a temporary digital detox -- no screens for six months. No television, no computer games, no internet, no phones, no iPods. The Winter of Our Disconnect is their story, and a rumination on the effect that being permanently plugged in has on us all.

Times change fast in the world of technology. In 2009, being deprived of their iPods was a major hurdle. In 2019, I'm not sure that iPods even exist any more. Now music and podcasts are streamed through our phones. Maushart's kids didn't care that much about losing their phones, because back then phones didn't do as much as they do now. I laughed at the fact that Maushart's elder daughter, at 19, was addicted to Facebook. Ten years later, no 19 year old in their right mind would go anywhere near Facebook (so I'm told). Facebook is for nanas!

The details may have changed, but the central lessons are still valid, in fact more valid than ever. Boredom is good for us. Without a screen in the way, we can see the real world more clearly. Constant distraction is robbing us of deep concentration. Hanging out with our friends is more rewarding than social media. Access to screens stops us sleeping properly.

The three teenagers (heavily bribed to take part) survived. Maushart's son picked up his neglected saxophone and embarked on a musical career. Her daughter rebooted her disordered sleeping patterns and hugely improved her mood and her health. And Maushart, with more time to reflect deeply on her life, decided to relocate the family back to her home, the US. (How the kids reacted to this decision is not recorded.)

When I talked to my own teenagers about this experiment, their reaction was swift and predictable. No way. Impossible. And sadly, I fear they might be right. I don't think the digital world we live in now is all bad, but it does come at a cost, and I'm not sure our kids even realise what that price is.

Times change fast in the world of technology. In 2009, being deprived of their iPods was a major hurdle. In 2019, I'm not sure that iPods even exist any more. Now music and podcasts are streamed through our phones. Maushart's kids didn't care that much about losing their phones, because back then phones didn't do as much as they do now. I laughed at the fact that Maushart's elder daughter, at 19, was addicted to Facebook. Ten years later, no 19 year old in their right mind would go anywhere near Facebook (so I'm told). Facebook is for nanas!

The details may have changed, but the central lessons are still valid, in fact more valid than ever. Boredom is good for us. Without a screen in the way, we can see the real world more clearly. Constant distraction is robbing us of deep concentration. Hanging out with our friends is more rewarding than social media. Access to screens stops us sleeping properly.

The three teenagers (heavily bribed to take part) survived. Maushart's son picked up his neglected saxophone and embarked on a musical career. Her daughter rebooted her disordered sleeping patterns and hugely improved her mood and her health. And Maushart, with more time to reflect deeply on her life, decided to relocate the family back to her home, the US. (How the kids reacted to this decision is not recorded.)

When I talked to my own teenagers about this experiment, their reaction was swift and predictable. No way. Impossible. And sadly, I fear they might be right. I don't think the digital world we live in now is all bad, but it does come at a cost, and I'm not sure our kids even realise what that price is.

Labels:

Australian women writers,

book response,

family,

non-fiction,

technology

11.10.19

Minnow on the Say

Philippa Pearce wrote one of my favourite books of all time, a book that had a huge impact on my imagination, Tom's Midnight Garden. I was aware that she'd also written Minnow on the Say, though I'd never read it; what I didn't realise was that Minnow was her first novel for children, published in 1955. When I found this copy in Brown & Bunting, I snatched it up.

Minnow on the Say is a lovely, very enjoyable, old-fashioned children's story, but it lacks the transformative brilliance of Tom's Midnight Garden. The Minnow of the title is a canoe, and the Say is a river, and the two boys on the cover, Adam and David, are searching for a lost treasure that is the only thing that will save the home of the canoe's owner, Adam. There is an enigmatic rhyme to guide them, penned by a mysterious ancestor, and Adam's grandfather's failing memory.

Adam's grandfather, old Mr Codling, is a poignant figure. Suffering from what we would now call dementia, he's trapped in a melancholy past, looking forward only to his son's return from the war. But his son is dead, and Mr Codling doesn't even recognise Adam, his grandson. The moment that stays with me, and reminds me most of Tom's Midnight Garden, is when old Mr Codling sees Adam in the moonlight and is joyfully sure that his son has at last returned home.

The treasure hunt itself is painfully slow and I doubt that a young modern reader would persist with the story. The Edward Ardizzone illustrations add greatly to the charm of the book -- when I think about it, I realise that Ardizzone illustrated so many of my childhood favourites (I'm thinking particularly of Nicholas Stuart Gray's creepy and moving Down in the Cellar). Why don't kids books have illustrations any more? (Answer: because it costs too much, I suppose. What a shame.)

Minnow on the Say is a lovely, very enjoyable, old-fashioned children's story, but it lacks the transformative brilliance of Tom's Midnight Garden. The Minnow of the title is a canoe, and the Say is a river, and the two boys on the cover, Adam and David, are searching for a lost treasure that is the only thing that will save the home of the canoe's owner, Adam. There is an enigmatic rhyme to guide them, penned by a mysterious ancestor, and Adam's grandfather's failing memory.

Adam's grandfather, old Mr Codling, is a poignant figure. Suffering from what we would now call dementia, he's trapped in a melancholy past, looking forward only to his son's return from the war. But his son is dead, and Mr Codling doesn't even recognise Adam, his grandson. The moment that stays with me, and reminds me most of Tom's Midnight Garden, is when old Mr Codling sees Adam in the moonlight and is joyfully sure that his son has at last returned home.

The treasure hunt itself is painfully slow and I doubt that a young modern reader would persist with the story. The Edward Ardizzone illustrations add greatly to the charm of the book -- when I think about it, I realise that Ardizzone illustrated so many of my childhood favourites (I'm thinking particularly of Nicholas Stuart Gray's creepy and moving Down in the Cellar). Why don't kids books have illustrations any more? (Answer: because it costs too much, I suppose. What a shame.)

Labels:

antique fiction,

book response,

children's books

9.10.19

How Bright Are All Things Here

I started reading Susan Green's lovely novel How Bright Are All Things Here about a year ago, but set it aside because there was a character with a depressed husband -- a theme that was a little too close to home at the time! Fortunately that particular situation has resolved itself and I was able to return, and I'm so glad I did. In fact I needn't have shied away so soon, as the husband's depression doesn't play a huge part in the story and (spoilers) it also resolves happily in the end.