Children's & YA v Adult

Wow, I read more adult books than children's and young adult! Has the tide turned? Am I growing up at last? I must admit that I enjoyed more adult books than kids' books this year -- and the books I hated were all YA (not naming any names...)

Female v Male authors

As usual, the ladies have it -- but not by much. I read two books with a mixture of male and female contributors. I might need to start a non-binary category, if I can find some books by non-binary-identifying authors.

Fiction v Non-fiction

Quite a bit more non-fiction this year, though fiction is still clearly dominant. I had a couple of binges which might account for the swelling of the non-fiction ranks: I read a lot of Oliver Sacks books early in the year, and then later on I had a binge on WWII and post-war memoirs and non-fiction. I also read a handful of books about the English language.

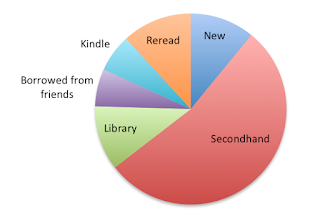

Sources

Oh my God!! My secondhand book spending habit is clearly out of control! I knew it was bad, but I've been in denial about how bad it actually is... The red part is taking over the whole pie! I cannot let my husband see this. Clearly I have a major problem. And this was supposed to be the year when I didn't buy any more books till I finished the ones I had!

Nationality

Okay, I may as well move to the UK and have done with it. I seem to have a British reading-soul. Must be all those English children's books I grew up with that I've never managed to shake off. Thank God for Elena Ferrante and Tove Jansson or this chart would look even worse.

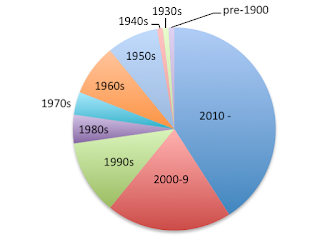

Publication date

Clear majority of books were published in this century, so maybe my addiction to antique books is not as bad as I feared. I caught up with some late 20th century children's books that I was too old for when they were first published, so I'm filling in some gaps there. I'm happy to say that most of the newest publications were by Australian authors, and mostly YA and children's books. #LoveOzYA!

Favourite books of 2017

Perhaps the single book that made the greatest impression on me this year was Planet Narnia by Michael Ward, a scholarly, enlightening and convincing examination of the possible astrological pattern behind the Chronicles of Narnia.

I was delighted to discover the books of Kate Atkinson, and thoroughly enjoyed both the Jackson Brodie series and Life After Life. There are still titles of hers I haven't read, and she has a new novel out next year.

Bruce Pascoe's Dark Emu made me angry.

Bill Konigsberg's Openly Straight made me laugh.

John Lanchester's Family Romance made me cry.

Michelle Cooper's Dr Huxley's Bequest taught me loads about the history of medicine.

I had two extraordinary reading experiences this year. First was Alan Garner's Boneland (so good I read it twice) and the accompanying Guardian blog, and my subsequent delving into Garner's back catalogue.

Second was the on-going Twitter read-through of Susan Cooper's The Dark Is Rising, #TheDarkIsReading, which is being held over the actual time frame of the book, from midwinter's day to Twelfth Night. More about this later.

Happy 2018 to you all and may your year be filled with books!